Katharina Hoins, Zeitungen. Medien als Material der Kunst

Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2015

broschiert, 318 Seiten

ISBN 978-3-496-01485-0

Das Rascheln beim Blättern der dünnen Seiten, die straffende Handbewegung, die das zerknitterte Papier glatt streift und dabei – wie man immer erst zu spät merkt – die Finger schwärzt: Jene charakteristischen Materialzüge, die sofort ein gezielt haptisches Bild zeichnen, setzt Katharina Hoins als Ausgangspunkt für ihre Untersuchung der Zeitung als Material der Kunst. Quer durch das 20. Jahrhundert verfolgt sie in ihrer breit angelegten Forschungsarbeit künstlerische Positionen, theoretische Vektoren und mediale Umbrüche. Hoins steckt damit erstmals jenes weite Territorium ab, das die Zeitung als Material im Diskursfeld der Kunst eröffnet.

Mit Nachdruck situiert die Autorin ihre Dissertation, die sie als „Beitrag zur interdisziplinären Debatte über die Materialität der Medien“ (10) verstanden wissen möchte, im Spannungsfeld von Medienwissenschaft und Kunstgeschichte. Grundlegendes terminologisches Instrumentarium hierfür sind drei zentrale Begriffe: Materialität, Medialität und Semantizität. Der Materialitätsbegriff wird als eine Ausprägung jenes Oszillierens zwischen physischem Trägermaterial und dem aus und auf ihm Geschriebenen eingeführt. Medialität wiederum bezeichnet, in Abgrenzung zur Kommunikation abseits technischer Medien, die jeweilige Form der Vermittlung: Durch ihr spezifisches Merkmalsgefüge und dessen Inszenierung wird die Zeitung von anderen Vermittlungskanälen unterschieden. Den Begriff der Semantizität entlehnt Hoins dem Vokabular Jan Assmanns: Die Verbindung von „direkt Bezeichnetem“ und „weniger konkret dinglich Bedeutetem“ sieht sie als Qualität des Assmann’schen Begriffs an, mit dem bezeichnet wird, „dass und welchen Inhalt sie [die Zeitung] über Schrift und Bild vermittelt“. (18) Insgesamt wird in der Einleitung ein klares Ausgangsfeld für die folgende Untersuchung formuliert, deren theoretischer Schwerpunkt eindeutig in der Medienwissenschaft liegt. Erstaunlich ist die Reihenfolge, die den drei zentralen Begrifflichkeiten eingeschrieben ist: für die Medialität ist die Materialität als Bedingung gesetzt, für die Semantizität ist die Lesbarkeit grundlegende Voraussetzung. Hoins betont zwar, dass sie in ihrer Arbeit kein chronologisches, sondern ein systemisches Vorgehen verfolgt – jedoch ist damit nicht die Frage nach einer aus der Begriffssetzung hervorgehenden Reihenfolge beantwortet.

Mit der Technik der Collage wird das erste Kapitel eingeleitet: Zunächst liegt der Fokus auf dem Ausschneiden, der Transformation und Rekonstellation. Schnell jedoch wird anhand der Berliner Dadaisten die „relative Rückführbarkeit der Inhalte“ (25) wichtig: Aufgrund der offensichtlichen Herkunft des Zeitungsausschnitts – der nicht nur Teil eines (medialen) Alltagsgeschehens, sondern auch Teil einer bestimmten, also dechiffrierbaren Presseöffentlichkeit ist – legte etwa Hannah Höch die „Konstruktionsprinzipien“ (27) ihrer Collagen offen und generierte dadurch ein Bild mit gezielten Bezügen zum Außen. In der zeichentheoretisch geprägten Besprechung der Werke von Georges Braque, Juan Gris und Pablo Picasso betont die Autorin die besondere Stellung, die Zeitungsausschnitte in dieser Konstellation einnehmen, da „sie gleichsam ein Scharnier […] bilden […] und sowohl Gegenstand sind als auch Text ins Bild bringen.“ (43) Dieser Weg führt sie weiter zu Robert Rauschenberg, anhand dessen Black Paintings die Diskussion in das Diskursfeld von Figur und Grund beziehungsweise Trägermaterial erweitert wird. Die Zeitung wird hier als Sediment gedacht und stellt damit – wenngleich durch den Farbauftrag unsichtbar geworden – einen essentiellen Bestandteil des Gemäldes dar: „Papieruntergrund und Zeichensubstanz verschmelzen zu einem pastosen Relief, zu einem untrennbaren Amalgam.“ (47) Dieser Amalgamierung stehen „zeitungssichtige“ Arbeiten gegenüber, in denen die Zeitung als Material sichtbar bleibt: „das Changieren zwischen Figur und Grund“ scheint Rauschenberg, so Hoins, regelrecht zu provozieren. (51) Im Dialog mit Arbeiten von Willem de Kooning, Jasper Johns und Franz Kline zeichnet die Autorin ein umfassendes Bild unterschiedlicher, jedoch zeitlich parallel laufender künstlerischer Strategien im Umgang mit Zeitung als Bild-Material. Leider kommt hier die Diskussion um die Ausdehnung der Malerei in den Realraum, insbesondere mit Blick auf die aufkommende Objektkunst und den Diskurs um die Medienspezifität, etwas zu kurz. Interessant ist die ausführliche Besprechung von Rauschenbergs Hoarfrost Serie (Abb. 1), in der Rauschenberg die Druckerschwärze vom Zeitungspapieruntergrund auf verschiedene Gewebe und Stoffe übertrug und damit eine „Verwandlung“ der Zeitungen vollzog. (58)

Abb. 1: Robert Rauschenberg, Glacier (Hoarfrost), 1974, Transfer auf Satin und Chiffon, mit Kissen, 304,8 x 188 x 14,9 cm, Houston, The Menil Collection.

Als theoretisches Pendant zu den künstlerischen Entwicklungen wird schließlich Marshall McLuhan herangezogen: Auf Basis der „Rekordausgaben für Werbung seit dem Wirtschaftsboom der Nachkriegszeit und [der] Diversifizierung der Medien“ hat sich dieser in den 1950er Jahren einer wissenschaftlichen Analyse der „Phänomene der Mediengesellschaft“ angenommen. (70) Spannend ist in diesem Kontext McLuhans Vergleich des „industriellen Menschens“ mit einer Schildkröte, die nichts von ihrem Panzer weiß. Diese im Inneren „befangene“ oder vielmehr gefangene Wahrnehmung entspräche der praktischen Anschauung des Menschen, der die Schildkröte eher verspeisen, denn ihren Panzer bewundern würde: „Derselbe Mensch würde lieber in die Zeitung eintauchen, als irgendein ästhetisches oder intellektuelles Verständnis ihrer Beschaffenheit und Bedeutung zu besitzen.“ [1] Mit McLuhan kommt Hoins zu dem Schluss, dass sich die Pop-Art-KünstlerInnen der Materialität und Medialität der Medien zuwandten und „mit Motiven aus der Populärkultur“ dazu aufforderten, „die Beschaffenheit der Medien in den Blick zu nehmen“. (71) Ähnliche Bestrebungen attestiert die Autorin auch der Malerei in Westdeutschland; sie analysiert – vor dem Hintergrund einschlägiger Vertreter der amerikanischen Pop-Art – Gemälde von Sigmar Polke, Wolfgang Tillmanns und Gerhard Richter. Abschließend werden die Bestrebungen der „Ideenkunst“ Joseph Kosuths thematisiert, der „das Phänomen der relativen Durchsichtigkeit der Zeitung […] als neutrales und transparentes Medium, das der Betrachter in seiner Materialität und Medialität zu ignorieren gewohnt sei“, aufgreift. (84) Die Zeitung, so wird Kosuth paraphrasiert, könne für die Konzeptkünstler als neutraler Informationsvermittler fungieren, als „bereits gestaltete – und damit quasi neutrale – Form der Vermittlung ihrer Ideenkunst“. (84) Damit wird bereits im ersten Kapitel ein breites Spektrum künstlerischer Positionen aufgespannt, die „von der Amalgamierung über die breite Fächerung bis zum Versuch der Ablösung“ reichen. (89)

Das zweite Kapitel wendet sich der Inszenierung von „Räumlichkeit, Körperlichkeit und direkte[r] Berührung mithilfe der Zeitung als Material“ zu. Um der zeitgenössischen Medienentwicklung Rechnung zu tragen, verknüpft Hoins die Analyse einzelner Arbeiten mit Wahrnehmungstheorien und dem Fernsehen, dessen Entwicklung zum neuen Leitmedium „als Bezugsrahmen [dient], da das Konkurrenzmedium wesentlich zur Veränderung der Bewertung und Wahrnehmung der Zeitung führte.“ (93) Am Horizont des Kapitels steht die „Verklammerung von Raum und Körper“, die, der Autorin zufolge, auf eine bewusste Wahrnehmung dieser Kategorien zielte. (94)

Mit Raoul Hausmann und George Grosz stehen zunächst die künstlerischen Strategien des Berliner Dadaismus im Zentrum, die die Verzerrtheit der Wirklichkeitsbeschreibungen durch die journalistischen Medien zu entlarven und zu hinterfragen suchten. Dabei wird erneut die politische Agenda der Dadaisten virulent, was angesichts der einleitenden Fokussierung auf Körperlichkeit und Raum durchaus überrascht. Etwas verwirrend ist hier, dass das Erleben und die Wahrnehmung als zentrale Rezeptionsmodi im Sinne eines Lesens und bildlichen Identifizierens von journalistischen Produkten verstanden werden. Die körperliche und räumliche Erfahrung hingegen – etwa von Installationen oder Performances – gerät zunächst teilweise in den Hintergrund.

Als theoretische Referenz hinsichtlich der „Abdichtung der Information gegen die Erfahrung“, wie sie in journalistischen Printmedien der Fall sei, wird in diesem Kapitel Walter Benjamin herangezogen. Dessen Blickwinkel auf das Zeitungswesen als Ort der Schilderung „vermeintlicher Erlebnisse von ‚schockförmiger‘ Ereignishaftigkeit“ wird mit den Bestrebungen der Dadaisten enggeführt. (99) Die etwas unvermittelte Bezugnahme auf Martha Rosler dient der Explizierung künstlicher Distanzierung von Kriegsereignissen durch deren mediale Vermittlung. Hoins legt im Folgenden präzise die historische Geschichtsauffassung in der Zeit um den Ersten Weltkrieg dar; daran wird deutlich, inwiefern das möglichst unvermittelte, direkte Nah-Erleben auch in der medialen Situation der Zeit als erstrebenswert galt. Durch die Konzentration auf den Dadaismus ergibt sich eine Fokussierung auf Krieg und Kriegszustände; derlei gesellschaftspolitische Ausnahmesituationen werden als Gradmesser für die realitätsabbildende Funktion der Medien herangezogen.

Abb. 2: Johannes Baader, Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama, 1920, Assemblage mit verschiedenen Materialien, darunter Zeitungen, Ofenrohr, Schaufensterpuppe, Zahnrad, Plakate, wohl über 2 m Höhe, nicht erhalten.

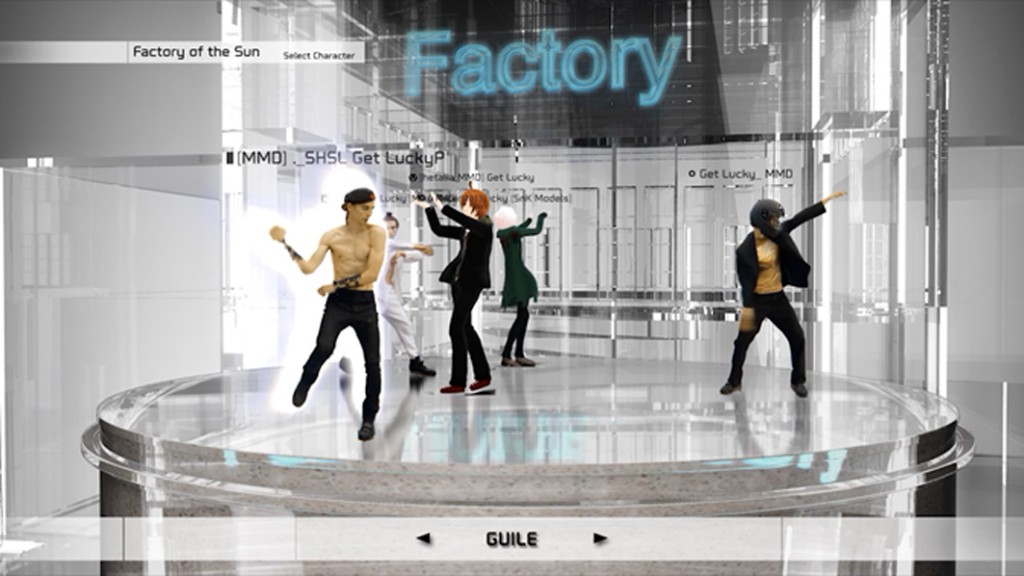

Unter dem Gesichtspunkt der Authentizität wird Robert Gobers Arbeit für die Zeitschrift Parkett mit dem ikonischen Kaffeetassenabdruck besprochen: Hier sei eine „Installation von Präsenz“ vorgenommen worden – eine Formulierung, die die Autorin von Rosalind Krauss entlehnt. Auf die körperliche Erfahrung der Installationssituation kommt Hoins schließlich anhand von Allan Kaprows Arbeit Apple Shrine (Abb. 2) zu sprechen. Die Wände dieses Environments waren mit zerknüllten Zeitungen tapeziert, „so dass die Besucher beim Betreten […] zwangsläufig in körperlichen Kontakt mit dem Papier gerieten“. (113) Am „Ende des labyrinthartigen Ganges“ konnten die BesucherInnen wählen: zwischen essbaren und künstlichen Äpfeln. Die Beleuchtungssituation im Inneren erschwerte jedoch die visuelle Unterscheidung der beiden Sorten: Mit Jeff Kelley sieht Hoins daher in den Äpfeln eine „metaphor of the relation of truth to appearances, originals to copies, pleasure to abstinence and body to mind“[2] verkörpert, die – wie die omnipräsente, exaltierende Zeitungstapete – dazu anregte, diese Polaritäten im Kaprow’schen Schrein zu reflektieren. (114)

Es folgt ein Exkurs in die vorwiegend amerikanische Mediendebatte über das neue Leitmedium Fernsehen, die sich auch als interessante Parallelisierung zum medienreflexiven Diskurs über die Zeitung lesen lässt. Hoins fasst treffend zusammen und liefert einen umfangreich recherchierten Überblick über die teilweise durchaus kontroversen Positionen zu den medialen Entwicklungen der 1950er und 1960er Jahre. Hier bespricht die Autorin auch partizipative Kunstformen und deren performativen Einsatz von Zeitungen – die nun, im Angesicht der televisuellen Welteroberung, zu einer Inkarnation des Wirklichen, des Materiellen und damit des buchstäblich Greifbaren geworden sind. Zeitungen, vormals unter Beschuss aufgrund vorgetäuschten Erlebens und vermeintlich unvermittelter Realitätswahrnehmung, figurierten knapp fünfzig Jahre später bereits als skulpturale Interventionen und als Mittler und Träger von Körperlichkeit, so ließe sich das zweite Kapitel summieren.

Im dritten Kapitel fokussiert Hoins die Bezugsdimension Zeit, die für den Materialeinsatz von Zeitung als zumeist tagesaktuellem Medium im Kunstkontext grundlegend relevant ist: Für die Kunst der zweiten Hälfte des Jahrhunderts sei die Zeitung das Medium der Vergänglichkeit beziehungsweise des Verfalls schlechthin, dessen Aktualitätsbezug durch das Fernsehen überholt wurde.

Zunächst erläutert Hoins aber die „Organisation und Zusammenstellung der Inhalte innerhalb der Zeitung, also Aspekte ihrer spezifischen Medialität“, die sie als „Simultaneität“ bezeichnet. (145) Die Berliner Dadaisten – ein besonderer Fokus liegt hier auf den Arbeiten von Hannah Höch – verfolgten eine „Überspitzung des Prinzips der Gleichzeitigkeit“ und versuchten mit ihren Collagen eine förmlich exzessive, „gesteigerte Simultaneität“ zu erreichen. (146) Damit rückt auch die Geschwindigkeit der Produktion – sowohl der journalistischen als auch der künstlerischen – in den Fokus: Die Brisanz der Zeitung erübrigt sich zumeist mit Tagesende; dies bedingt eine schnelle Produktion, die sich wiederum im Vergänglichkeitspotenzial des Mediums selbst niederschlägt. Zentral bleibt für Hoins auch in der Aktualitätsdebatte der mediale Konkurrenzkampf zwischen Zeitung, Rundfunk und Fernsehen.

Mit Vostells Zeitungsaktionen – ritueller Zeitungsverkleinerung, Veränderung des Aggregatzustands – und Beuys‘ Zeitungsverspeisung wird der Aspekt des Organischen und damit der Naturbezug thematisiert. Wenn Hoins ausführt, wie Vostell und Beuys durch die Zerhackung beziehungsweise das Verspeisen die Materialität der Zeitung gegen ihre Semantizität „ausspielen“, bleibt der Mehrwert ihrer Terminologie durchaus unklar. Eine andere Form der Zerstörung des kulturellen Produkts Zeitung im Kontext eines Kunstwerks findet sich bei den benagelten Zeitungen von Günther Uecker: Die Autorin zielt hier auf die thematische Durchlässigkeit zwischen der Semantizität und der Materialität der Zeitung ab. Gerade wenn sie die Körperlichkeit des Eingriffs betont und dafür sogar die „Metapher für den menschlichen Körper“ bemüht, stellt sich die Frage, warum Uecker nicht schon im zweiten Kapitel eingeführt wurde. Ein längerer Exkurs führt daraufhin zu Johannes Baaders Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama (Abb. 3): Angesichts der ausführlichen Besprechung und der quantitativen Überlast des Dadaismus verstärkt sich der Eindruck, dass hier Hoins‘ tatsächliches Forschungsinteresse liegt.

Abb. 3: Allan Kaprow, Apple Shrine, 1960, Installation mit Zeitungen, Maschendraht, Holzleisten, Äpfeln, Kunststoffäpfeln, Judson Gallery, New York, nicht erhalten.

Das abschließende vierte Kapitel vereint unter den drei Verben „Montieren, Kommentieren, Einschreiben“ noch einmal verschiedenste Zugänge zur Zeitung: als – bearbeitbares, formbares und rekonfigurierbares – Material, als Gegenstand, der in einer zeithistorischen Wirklichkeit konsumiert und produziert wird, aber auch als Vermittlungsform des Geschriebenen.

Hoins leitet das Kapitel mit einem längeren Absatz zur Montage ein, deren Form schließlich auch zentral für die dringliche Diskussion um die Autorschaft ist. Den Modus der Collage reflektierend resümiert sie verschiedene Spielformen der Signatur, in der sich die Produktionsform und die Herstellungsmechanismen eben jener Kunstformen widerspiegeln. Anhand der Arbeiten von John Heartfield und George Grosz werden die gesellschaftshistorische Kontextualisierung und die sich verändernden Produktionsmechanismen erläutert: die sich durchsetzende „Taylorisierung“ (206), die Grosz auch in der Kunst ausmachte, und die zunehmend seriell-industrielle Produktion. In Anknüpfung an die bereits zuvor eingeführte Diskussion rund um das Produkt werden künstlerische Verfahren behandelt, die sich der Produziertheit des Menschen durch die Entwicklung der Presse annahmen. Davon ausgehend werden die Dimension der Autorschaft und damit die Frage nach der persönlichen Biographie in den Blick genommen: An eben jener Schnittstelle setzt Hoins die Arbeiten Jean Dubuffets an, der wiederum den persönlichen Schriftzug und damit die Handschrift prominent der gedruckten Zeitung entgegensetzt. Insbesondere in formaler Hinsicht erscheint die daran anschließende Thematisierung des Dresdner Künstlers Hermann Glöckner schlüssig; naheliegend ist auch der Vergleich der Dubuffet’schen Messages mit den zeitnah entstandenen Werken Glöckners, der im politischen Kontext der DDR ähnliche künstlerische Strategien der Übermalung und Einschreibung verfolgte. Mit Dieter Hacker und Gustav Metzger verfolgt Hoins schließlich künstlerische Strategien der „Funktionsstörung von Öffentlichkeit“ weiter. (233) Erstaunlich ist, dass – gerade im Zuge der Abhandlung der diskutierten Kategorien von Öffentlichkeit beziehungsweise Gegenöffentlichkeit – Rodney und nicht Dan Graham als abschließende Position des Kapitels gewählt wurde.

Im Resümee unterstreicht Hoins den Mehrwert ihrer Analysekategorien, die allerdings im Zuge der Lektüre zunehmend aus dem Fokus gerieten. Dass ihre Untersuchung zeigen konnte, dass die besprochenen Arbeiten jeweils im „Kontext historischer Mediendiskurse“ (239) stehen, überrascht dabei wenig. Zurecht wird die präzise Analyse dieser Kontextualisierung jedoch als zentrale Erkenntnis der Publikation betont.

Zusammenfassend lässt sich festhalten, dass Hoins‘ Band erstmals zentrale künstlerische Strategien im Umgang mit dem Material Zeitung in der amerikanischen und westeuropäischen Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts versammelt. Die Publikation zeichnet sich durch einen ausnehmend breiten, facettenreichen Beispielkatalog aus, in dem der Berliner Dadaismus einen unerwartet großen Teil einnimmt. Trotz dieser großen Bandbreite ihres Forschungsmaterials gelingt es der Autorin, fundierte Analysen einzelner Positionen vorzunehmen. Hoins inkludiert in ihre Anthologie auch – und das muss in besonderem Maße positiv verzeichnet werden – künstlerische Positionen, die sich abseits des kunsthistorisch-institutionalisierten Kanons bewegen. Der überwiegende Teil der Untersuchung behandelt jedoch männliche Künstler: Inwiefern diese Auswahl tatsächlich der historischen Faktenlage – man denke etwa an Barbara Kruger, Linder Sterling oder Sanja Iveković[3] – geschuldet sein kann, muss fraglich bleiben, da die Autorin selbst darauf nicht eingeht.

Hoins‘ betont non-chronologische, systemische Vorgehensweise eröffnet Bezüge und Sichtweisen, die andernfalls nicht virulent geworden wären. Ihre Methode bedingt allerdings auch zahlreiche historische Sprünge, die sich mancherorts produktiv und spannend, andernorts jedoch verkürzend und verunklärend auswirken. Der zunehmend akuter werdende Wechsel zwischen den doch sehr verschiedenen historischen Settings, die das 20. Jahrhundert in Europa und Nordamerika durchläuft, erfolgt leider streckenweise auf Kosten der inhaltlich-thematischen Stringenz der Argumentation und resultiert in abrupten Übergängen. Eine durchgängig dezidiertere Strukturierung durch die anfänglich eingeführten Begrifflichkeiten Materialität, Medialität und Semantizität wäre daher – auch hinsichtlich der konkreten Einsetzbarkeit der Termini – wünschenswert. Für die Kunstgeschichte ist Hoins‘ Dissertation aber in jedem Fall als eine umfassende, facettenreiche und daher durchaus empfehlenswerte Publikation anzusehen, die insbesondere für den deutschsprachigen Raum eine präzise recherchierte Diskussion der Zeitung als künstlerisches Material im 20. Jahrhundert vorstellt.

[1] Hoins zitiert hier eine deutsche Übersetzung (Marshall McLuhan, Die mechanische Braut. Volkskultur des industriellen Menschen, Amsterdam 1996) von McLuhans Essay zur „Titelseite“ aus 1951: „Der industrielle Mensch ist der Schildkröte nicht unähnlich, die für die Schönheit des Panzers, der auf ihrem Rücken gewachsen ist, ganz blind ist. […] Diese im Inneren befangene Wahrnehmung stimmt mit der praktischen Anschauung des Menschen überein, […]. Derselbe Mensch würde lieber in die Zeitung eintauchen, als irgendein ästhetisches oder intellektuelles Verständnis ihrer Beschaffenheit und Bedeutung zu besitzen.“, Hoins 2015, S. 70.

[2] Hoins zitiert hier den originalsprachlich englischen Text von Jeff Kelley, Childsplay. The Art of Allan Kaprow, Berkeley, Los Angeles 2004.

[3] Ich danke Johanna Braun für zahlreiche weitere konkrete Hinweise.