Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War era, artistic works have reacted to the transformations, perceptions and effects on the fading memory of the socialist past. Curatorial projects like Interrupted Histories by Zdenka Badovinac in 2006[1], Progressive Nostalgia organised by Viktor Misiano in 2007[2], or more recently, Ostalgia by Massimiliano Gioni in 2011[3] and The Way of the Shovel: Art as Archaeology in 2013 by Dieter Roelstraete[4] in one way or the other dealt with the predetermined and transformative nature of memories. Localising and discussing the socialist experience became an important focus of many artists and curatorial projects, and only recently the web’s “ever-growing memory-banks (i.e. […] online encyclopedias, search engines, and the like […]”[5] have entered the realm of artists as historiographers, archaeologists or storytellers. In the last chapter of her book The Future of Nostalgia (2001), literature theorist Svetlana Boym makes a crucial remark on the status of memory in the digital age revealing her technological skepticism:

“Computer memory is independent of affect and the vicissitudes of time, politics and history; it has no patina of history, and everything has the same digital texture. On the blue screen two scenarios of memory are possible: a total recall of undigested information bytes or an equally total amnesia that could occur in a heartbeat with a sudden technical failure.”[6]

I would like to prove that the concept of memory has so tremendously changed that a strong differentiation between virtual memory and cultural memory[7] has lost its validity. When Boym talks about “computer memory” as if it is being hosted in a virtual non-place, this seems to be an assertion hard to maintain because we have learned that the digital and the ‘real’ merge into ever new forms and devices.[8] Within a condition in which the virtual is no longer considered as separate and ‘unreal’, this paper traces the transformation of cultural memory on socialism in times of digitisation and of “too many histories,” as cultural theorist Jan Verwoert describes the new situation after 1989.[9] Identifying artistic video installations as cinematographical spaces or “digital topographies,”[10] to use artist Hito Steyerl’s expression, which are dedicated to reactivate and choreograph past events, one can assume that the processes of cultural memory have changed simultaneously with the meanings of the word “virtual.”[11] Apparently, memory has undergone a process of transformation ranging from the documentary approach to practices of reenactment, to today’s prevalent performative, linguistic and narrative experiments in distinct audio-visual installations. Consequently many video works become increasingly disloyal to facts and gain independence from historical accuracy—first, because their conceptualisation is more and more informed by human and digital second-hand sources and furthermore because the experimental performing of the socialist memory within video works and their environments is transgressing the antagonism between the historical and the imaginary.[12]

We are indeed already in the midst of Boym’s memory scenario in which her “undigested information bytes” flood the popularised visual databases of socialist history, linked together into group memory systems like computers logged into networks.[13] New technological habits and the temporal distance to the past undoubtedly affect the way socialist experiences are approached. Therefore the questions in this respect must be: How is the experience of the socialist past reflected upon in contemporary video installations and is there something like a digitisation of memory happening within them?

By exemplarily focusing on two video installations which I understand as mnemonic topographies in the light of the socialist past, Anri Sala’s Intervista (Finding the Words) (1998) and Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (2015), this paper investigates how post-socialist memory has changed in contemporary video works since the late 1990s.

Mnemonic Topography I: Intervista (Finding the Words)

Ill. 1: Anri Sala, Intervista (Finding the Words), 1998, video still, single-channel video, stereo sound, colour, 26:39 min.

The iconic 1998 video work Intervista (Finding the Words) by Albanian artist Anri Sala (* 1974 in Tirana) has become one of the best known and most circulated artworks reflecting the post-socialist transition in the 2000s[14] as it deals with the biography of the artist’s mother as a kind of “model biography.”[15] The story of the film—considered as typical for the post-socialist experience—is structured as follows: some years after the end of the communist regime in Tirana, Sala discovers an undeveloped 16 mm film in a box at his parents’ house. The artist takes the negative to Paris, develops and restores it. On the tape he recognises his mother at the age of thirty-two, giving an interview and posing with the state’s president and communist leader Enver Hoxha during an Albanian Youth Congress in the late 1970s. The key feature of this found-footage material is the missing sound, which was lost during its time in storage. Therefore Sala goes to a deaf-mute school in Tirana, where his mother’s spoken words are lip read to reconstruct her original speech. Sala adds the missing sound as a written text below the image and visits his mother to show her the restored tape (ill. 1). It turns out that in 1977 Valdet Sala was the former head of the communist “youth alliance,” firmly formulating propagandistic statements for the cameras of Albanian state television.

Like the complex, heterochronic “motion capture studio Gulag” in Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (which is the spatial setting of the video game at the center of her work), Sala gives an example of “transactive memory,” a memory that is kept outside of our bodies[16]: the 16 mm film in his parents’ house, stored away and subsequently ‘forgotten’ by the mother. Within their respective works, Sala and Steyerl both reflect the contemporaries’ dealing with the transformation and the necessity of creating spaces of remembrance and retrospection. Art historian Mark Godfrey puts the historical relevance of Intervista (Finding the Words) in a nutshell:

„In this Communist era, historical representation itself had been banished: one of the crucial aspects of the work was that Sala not only looked back, but retrieved the very possibility of retrospection.”[17]

Refusing the dominant, psychologising reading of Intervista—particularly the widely established thesis that the mother is working through her traumatic past—here, the character of retrospection gains more importance.[18] To explore the work’s inherent conceptualisation of memory, it is important to take into account the two-fold nature of nostalgia as a motor of looking at the past: its retrospective and prospective orientation. In the introduction to her book, Svetlana Boym clarifies that the consideration of the future, and the connection between personal and collective memory, strongly characterise her vision of nostalgia. She particularly aims at “unrealised dreams of the past” and speculates about their “direct impact on realities of the future” which explains nostalgia’s being both retrospectively and prospectively structured.[19] But where is the prospective aspect in Sala’s individualised mnemonic topography exposing his mother’s private living room?

Sala’s work was produced in the 1990s, a time when, according to art historian Edit András, “the new democratic countries tried to clean up the ideologically polluted public sphere with its powerful images by demolishing statues, removing icons […] and renaming streets and squares […].”[20] This decade of clean-up and forgetting was also accompanied by an unwillingness to speak about the socialist past, and therefore András situates the emergence of Sala’s video work in an unpragmatic “phase of denial and rejection,”[21] at the core of this amnesic period in the 1990s. Hence, Sala produced a video work, which actually is highly prospective in that it is based on the idea that the process of speaking about the socialist experience and heritage has begun and will ensue in almost all Central and Eastern European living rooms. If one follows art historian Bojana Pejić, the creation of a “geographical map” with “newly shaped borders” can be seen as influential as the processes of “naming and renaming” and “finding the words” in the post-communist discourse.[22] While “intervista” is the Albanian word for interview, the title in parentheses, “finding the words,” leads to the impression that the lost words have to be retrieved in order to give a voice to the past. Excavating and reconstructing the 16 mm videotape and its audio track in the video work, Sala provides an example for a “reflective nostalgia”[23] which points towards the future and raises awareness for the collective framework of memory, because his mother’s life story is deeply interwoven with a societal system and a past community of political leaders. The experience of the “total break with an established social normality” after 1989 has not only affected Sala and his mother,[24] it also represents an impression of almost every citizen of Albania, of the people from the former “East” and also of many people from the former “West.” The artist understood that his mother’s life story as well as his curiosity and longing for truth are supra-individual phenomena; Intervista uses a personal perspective to raise an awareness for the “breakdown of language”[25] after the end of the Cold War and for the growing future responsibility to build new narratives from forgotten cultural artefacts like the film reel in Salas work. Thus, it is not without reason that since the 2000s art historians have been speaking about the ‘return of memory’ within visual art[26] because during these years one could have stumbled upon “a trace, a detail, a suggestive synecdoche”[27] leading to the socialist history in domestic and public places at any moment.

In Sala’s early video work of the late 1990s we discover an actually existing house, a building, still hosting archaeological remains of the socialist past. The system’s collapse is still present and a disturbing melancholia has impregnated the video’s imagery and its documentary aesthetics. Although this drama lies in the past and is therefore invisible, it has left rare material evidences like the discarded 16 mm film in the box. The filmic demonstration of the material and the interactions of mother and son mostly take place in a private middle-class apartment of the late 1990s. Several breakdowns of the mother’s speech, the grainy video quality and the close-ups of her face strengthen the effect of authenticity and of a realistic possibility of successfully digesting or processing the information—a promise that Hito Steyerl’s video work is at no point intending to give. Accordingly, Intervista (Finding the Words) is a video work which subtly conveys that the indices and sores can be traced back, narrativised and processed. On the contrary, what we will find in Factory of the Sun is a concept of memory that is committed to “unrealized possibilities, unpredictable turns and crossroads,”[28] but also to an “amalgamation of past and future.”[29] Although we also have a life story in the center, namely the one of the protagonist Yulia (and by implication that of her brother, aunt, parents, and grandparents), this video installation establishes a multi-temporal, fanned out topography, which is scattered into various imaginary, ‘real’ and virtual topoi.

Mnemonic Topography II: Factory of the Sun

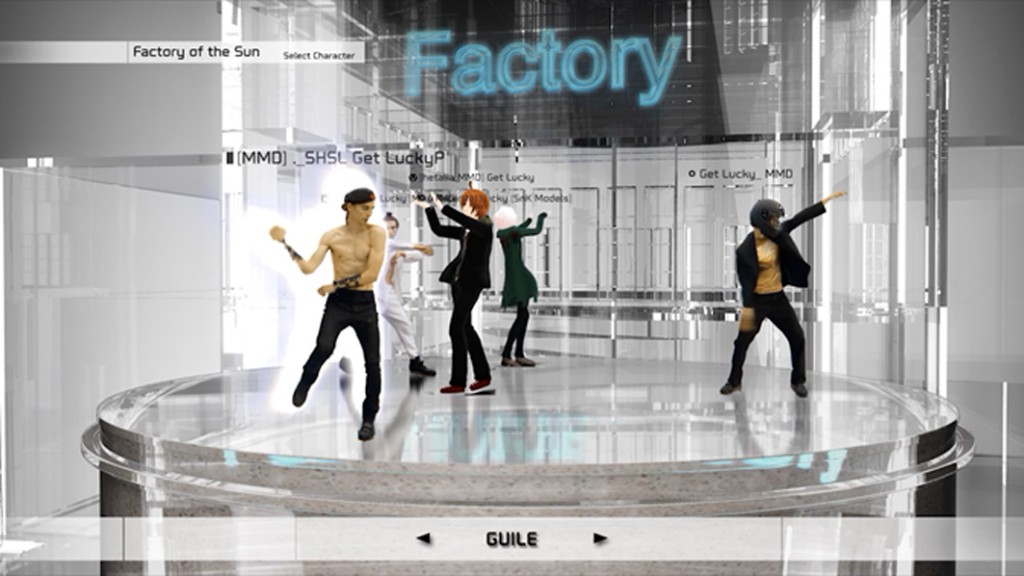

Ill. 2: Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015, video still, single-channel HD video, stereo sound, colour, 22:56 min.

Hito Steyerl calls the informational and interrelated spaces in the World Wide Web “digital topographies,” that reflect the new geographies of globalisation and the structure of the web.[30] In Factory of the Sun (2015), Steyerl develops a topographical scenario on a “holodeck” that is related to the retelling of a personal story: the escape of the female protagonist’s Jewish-Russian family from Russia, and the story of her aunt growing up in the Soviet Gulag as an “orphan of the enemy.” After recounting her family’s emigration from Russia through Israel to Canada, the programmer and main character ‘outside’ the video game, Yulia, a white, androgynous woman in her mid twenties, introduces the claustrophobic “motion capture studio Gulag:” a precisely measured studio space for the recording of human motions, whose prisoners are surveilled, threatened and most presumably killed by laser drones of the Deutsche Bank. Yulia’s brother Michael and the other actors within the video game are condemned to absorb light and transform it into the physical energy of movements and dance. The energy is then being turned into light impulses within another digital space: the virtual reality of the computer game itself. Yulia describes the other human and digital actors’ mission as follows:

“At this point in the game, everything flips. It turns out, you are your own enemy, you have to make your way through a motion capture studio Gulag. Everyone is working happily, the sun is shining all the time, it’s totally awful.”

Step by step, the viewer gets familiar with the ideology and the down sides of this “motion capture studio Gulag,” that is characterised by the vital dependency from sunlight. He also meets Yulia’s brother, who in virtual ‘real life’ is a dancing star on Youtube. Throughout the video, he replicates himself into various Japanese anime characters with radical leftist political agendas. The movements of the video games’ main protagonist and forced labourer are thus tracked, recorded and synchronously reenacted by the animated characters that are dancing nonstop on the “holodeck.”

“Motion capture studio Gulag” is a hybrid conceptual term that connects two former, Cold War-inspired antipodes: the “Western,” futuristic motion capture technique, developed for video games, movies and TV series, and one of the darkest chapters of Soviet history, the Gulag forced labour camps which existed under Stalinism. In Factory of the Sun, there are several of Boym’s “undigested information bytes,”[31] temporal memory images that literally float through digital space in a disparate but nevertheless meaningful, transhistorical way: light bulbs, a silver laptop, golden Stalin busts, the heroically raised arms of a communist leader’s statue, a car, a drone, the NSA listening station Teufelsberg, the motion capture reflective markers, the anime characters and the Kremlin in Moscow. Thus, the “motion capture studio Gulag” suspends the concept of linear time, exemplifying a “world in turmoil”[32] in which historical events like the electrification, the digitisation, the Cold War’s East/West competition or the family’s migration story appear as mere movable global icons.

Ill. 3: Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015, installation view at 56th Venice Biennale, German Pavilion.

The brother’s staged “death” is certainly one of the most remarkable themes of the video work: one can see it coming all the way through, but in the moment it occurs the image is blackened. Earlier in the video, the brother rehearses his death several times, pretending he has been hit by a drone and sinking down. This simulation happens for the camera; his sister praises his performance and he repeatedly slumps down for the video game’s motion capture program—as if it would be important to record many different, ‘natural’ dying scenes for the benefit of the game.[33] In her writings, Steyerl states that drones “survey, track and kill” in the service of “a new visual normality—a new subjectivity safely folded into surveillance technology […].”[34] In Factory of the Sun, the new vertical distribution of power or the growing importance of “aerial views, 3-D nose-drives, Google Maps, and surveillance panoramas”[35] seems to be strongly related to the nature of financialisation, the “post-medium condition of the capital” which organises and controls social relations, as described by philosopher Kerstin Stakemeier with reference to economist Giannis Milios.[36] The video work’s labour camp scenario seems to be inspired by The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins and the story’s tributes who are responsible for freeing the citizens from oppression and poverty—only that in Factory of the Sun the president and the Capitol are replaced by a global company: the Deutsche Bank which is able to supervise social performances. The brother’s subjectivity gets introduced as one of a protester, a dissident who has replicated himself into digital activists, the anime characters Naked Normal, Liquid Easy, High Voltage or Big Boss Hard Facts (ill. 2); however the brother turns out to be a prisoner who is forced to produce sunlight for an anonymous empire, constantly persecuted and threatened by laser drones. His subjectivity does not completely merge in surveillance technology because it cannot be fully annihilated; with his revenants and their dancing moves he first appears to follow a secret agenda using light for posthuman and counter-hegemonic conversions and reversals. But although he and his digital replicants possess utopian sci-fi abilities such as multiple lives, time travelling[37] and superpowers[38], the visitor soon starts to learn that the dancing young opponents on the platform of Teufelsberg are detainees of the Deutsche Bank who have faced disastrous economical and political situations on a global scale. In the follow-up breaking news segment, a Deutsche Bank spokesperson inconsistenly admits the brother’s killing, smugly speaking of a “terrorist defence measure,” denying a liquidation for political or financial reasons.

In the exhibition catalogue The Future of Memory (2015), art historian and curator Nicolaus Schafhausen explains that in contrast to the conception of ‘real’ memories by which he means “memories of events and spaces we experienced personally, now we are being confronted more and more with the recall of experiences we have gained from virtual sources.”[39] Hence, in the digital age, we are observing two crucial transformations that influence the face and nature of cultural memory related to socialist times: virtual memory competing with ‘real’ memory; and the fading—in fact by now almost non-existing—socialist experience of the younger generation. This explains the new entanglement of the documentary and the virtual and the subsequent diminishment of ‘real’ experiences. These aspects influence today’s ‘art of memory’ in a profound way, because it can no longer be understood merely as an “art of recollection.”[40] Rather, I assume that the selected video work and video installation configure mnemonic topographies subtly connecting the growing digitisation and new technological possibilities with the more and more distant memory of the socialist past.

Overcoming the ‘Real:’ Virtual Mnemonic Topographies

In our two examples, memory takes two different paths: one is characterised by the illusion of an adaption (Sala), the other is influenced by a virtual simulation of the imagined past, present and future (Steyerl). The historiographical operation in today’s video art can therefore be understood as a process of constructing virtual mnemonic spaces through an active creation of familiar and unfamiliar spaces of remembrance. In a particular way, these localisations of images within chosen architectures help to make visible the absent and past forms and bodies as well as things and words, because it is only due to the mneme, the memorial technique, that they at all occupy certain localities.[41] If we read video installations like Factory of the Sun as virtual mnemonic topographies, one can envision these territories as mnemic zones in which memorisable sentences, forms, bodies and things get performed.

The appearance of new media art, and especially the video installation, makes a significant impact on the relationship between the work of art and the spectator. As I have pointed out, I understand video installations such as Factory of the Sun as virtual mnemonic topographies: a constellation of the exhibition space, the digital video narrative and the viewing subject that is involved into a pre-constructed cinematographic theater setup. Whereas Anri Sala’s Intervista (Finding the Words) can get screened, virtual mnemonic topographies require a specific environment in order to be viewed and are therefore usually created for darkened rooms—the so-called black box—, in which the viewer’s attention gets monopolised.[42] Art historian Charlotte Klonk argues that these dark spaces would produce a “bodiless, lost-to-the-world cinema spectator”[43] which merges with the increasing heterochrony of the fundamental narratives in a growing number of historiographical video works. In Factory of the Sun, for example, this “holodeck dreamscape”[44] is not only virtual in terms of its material nature, but also: “the result of an interaction between subjects and objects, between actual landscapes and the landscapes of the mind. Both are forms of virtuality that only the human consciousness can recognize.”[45] Virtuality also helps to discover the prospective quality of memories and of processes of remembrance, editing the works’ implicit temporal horizons: it opens up for modalities of the present and the future,—made possible by the above-named fusion of “actual landscapes and the landscapes of the mind.” Especially with regard to today’s ‘art of memory’ practiced by contemporary video art, the learning, mediation and experimentation with memory techniques set the ground for a better understanding of the web’s earlier mentioned multi-temporal and disordered “memory banks.”

Virtual mnemonic topographies hence generate an isolated space of an intermediary experience of the socialist past and impose it upon the spectator not only in terms of the darkened interior, but as well in the sense of transforming the ways of visualising the past in synch with new technological possibilities and display strategies. In Factory of the Sun, this transformation has been performed by placing the spectators within the expanded space of the video: sun loungers and beach chairs for the public are installed in front of the monumental video screen, whereas the entire room of the installation simulates the “motion capture studio” and is illuminated by the blue grid in the space (ill. 3). If in our two examples one finds that the virtual reality “holodeck dreamscape”[46] has replaced the immediate first-hand encounter with the ‘real’ experience of the past—what has happened to memory then? It has been transformed towards a framework for performing digitally stored records and narrations. In a time when digital images increasingly lose their intrinsic memorability[47], the spectator of virtual mnemonic topographies gets invited to a simulation of the imagined past and present, involving the second generation as narrator, programmer and protester.

[1] Her concept of “interrupted histories” suggests fragmented, individual histories that develop as parallel, unofficial histories while reflecting on and disturbing the dominant narratives of the past. See Zdenka Badovinac, Tamara Soban (eds.), Interrupted histories, Ljubljana 2006.

[2] Viktor Misiano and Marco Bazzini (eds.), Progressive nostalgia: contemporary art from the former USSR, Prato 2007.

[3] Ostalgia, curated by Massimiliano Gioni at the New Museum in New York in 2011, aimed to showcase an overview of artistic practices dealing with the socialist experience. There, Boris Groys and Ekaterina Degot both recognised a generational shift in artists’ approaches to the socialist past. See Jarrett Gregory, Sarah Valdez and Massimiliano Gioni (eds.), Ostalgia, New York 2011.

[4] The curator and art historian Dieter Roelstraete considers 1989 as a key date for the historiographic impulse in art: “The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapse of various communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe, and the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, mark the first clear milestones in this process […]. The post-Soviet condition is the primary subject of work by a sizeable number of artists who came of age in the late 1990s/early 2000s […].” Dieter Roelstraete, Field Notes, in: Sarah Kramer (ed.), The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art, Chicago 2013, pp. 14-47.

[5] Roelstraete 2013, p. 33.

[6] Boym 2001, p. 347.

[7] Cultural memory can be understood as a process which includes “an exchange between the first and second person that sets in motion the emergence of a narrative.” According to cultural theorist Mieke Bal these cultural recalls get performed with the help of cultural artifacts, visual arts, literature or film. See Mieke Bal, Introduction, in: Mieke Bal et al. (eds.), Acts of Memory. Cultural Recall in the Present, Hanover 1999, pp. vii-xvii, p. x.

[8] According to artist Boaz Levin and cultural theorist Vera Tollmann from the Research Center for Proxy Politics (RCPP), the internet definitely has a materiality—one of earth-girding data centers, undersea cables and routers—and they state that “the old demarcations between the human body in physical space and the so-called immateriality of the digital sphere are being superseded.” See Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann, The Body of the Web, in: Out of Body. Skulptur Projekte Münster 2017, frieze d/e, No. 23, Spring 2016, n. p.

[9] Jan Verwoert, Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art, in: Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 2007. URL: http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/pdfs/verwoert.pdf [27.03.2016]

[10] See Hito Steyerl, Leben im Licht-GULAG, in: Kunstforum International, Vol. 233, June 2015, pp. 274-281, p. 279.

[11] For an insight into the genealogy of the word “virtual,” taking a distance from the simulacral or immaterial, see Homay King (ed.), Virtual Memory. Time-based Art and the Dream of Digitality, Durham, London 2015, pp. 11-12.

[12] Examples: Irina Botea It is now a matter of learning hope (2014), The Bureau of Melodramatic Research (Alina Popa, Irina Gheorghe) Above the Weather (2015), Mitya Churikov, Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978) (2014), Phil Collins Marxism Today (Prologue) (2010), CORO Collective (Eglė Budvytytė, Goda Budvytytė, Ieva Misevičiūtė) Vocabulary Lesson (2009/2010), Xandra Popescu & Larisa Crunțeanu Guilty Yoga (2012), Aleksandra Domanović Turbo Sculpture (2010-2013), Lene Markusen Sankt. Female Identities in the Post-Utopian (2016), Almagul Menlibayeva, Transoxiana Dreams (2011), Henrike Naumann Triangular Stories (2012), Yves Netzhammer Das Kind der Säge ist das Brett (The Saw’s Child is the Board) (2015), Kristina Norman After War (2009), Sasha Pirogova House 20, Apartment 17 (2014), ŽemAt (Eglė Ambrasaitė, Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė, Noah Brehmer, Eglė Mikalajūnė, Domas Noreika, Aušra Vismantaitė) Imagining the Absence (2014), among others.

[13] According to sociologist Milla Mineva, there are many platforms specifically designed for remembering communism online. See Milla Mineva, Communism Reloaded, in: Maria Todorova et al. (eds.), Remembering Communism: Private and Public Recollections of Lived Experience in Southeast Europe, Budapest 2014, pp. 155-173.

[14] Intervista (Finding the Words) was shown in the group exhibition “After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe” at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne (1999), in the “Privatisierungen. Zeitgenössische Kunst aus Osteuropa” exhibition at the Kunst-Werke in Berlin and at the ZKM in Karlsruhe (2004-2005), in the “Gender Check” exhibition at mumok Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig and at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw (2009-2010), in the “…on the eastern front. video art from central and eastern europe” (2010) exhibition at the Ludwig Museum-Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest, in the exhibition “His master’s voice” at La Panacée-Centre de culture contemporaine in Montpellier (2015) and screened at the New Museum in the context of the solo exhibition “Anri Sala: Answer Me” in 2016, among many others. For Intervista (Finding the Words), he won the “Best Documentary Film Award” at the Entrevues Festival in Belfort (1998), the “Best Short Film Award” at the Amascultura Film Festival in Lisbonne (1998), the “Best Film Award” at the Estavar Video Festival in Estavar (1999), “Best Documentary Film Award” at the International Documentary Film Festival in Santiago de Compostela (1999), the “North American Premiere” at the Vancouver Film Festival in Vancouver (1999), the “Best Documentary Film Award” at the Williamsburg Brooklyn Film Festival in New York (2000) and the Best Documentary Film Award at the Filmfest in Tirana (2000).

[15] Verwoert describes that Intervista constructs a “penetrating biographical narrative […] to describe the recent history and current situation of Albania.” Jan Verwoert, Double Viewing: The Significance of the ‘Pictorial Turn’ to the Critical Use of Visual Media in Media Art, in: Ursula Biemann (ed.), Stuff it. The video essay in the digital age, Zurich 2003, pp. 24-33, p. 27.

[16] For a deeper understanding of the term “transactive memory,” see Daniel M. Wegner, Transactive Memory: A Contemporary Analysis of the Group Mind, in: Brian Mullen et al. (eds.), Theories of Group Behaviour, ed. , New York 1986, pp. 185-205.

[17] Mark Godfrey, The Artist as Historian, in: October, Vol. 120, Spring 2007, pp. 140-172, p. 144.

[18] Looking at the work’s history of reception, I consider this psychologisation of the mother’s character’s actions, the strong rejection of her speech, as indicative of one of the fundamental problems of the discoursification of post-socialist art. The art historian Edit András, for instance, understands the function of this video work as a “cry for help” of a “lost generation” and relates to the mothers’ description that her generation seemed to be “trapped in a dreaming machine.” See Edit András, The Future is behind us. Flashbacks to the Socialist Past, in: Edit András (ed.), Transitland: Video art from Central and Eastern Europe 1989 – 2009, Budapest 2009, pp. 209-221, p. 216.

[19] Boym 2001, p. XVI.

[20] Edit András, An Agent that is still at Work. The trauma of collective memory of the socialist past, in: Writing Central European Art History, Vienna 2008. URL: http://www.erstestiftung.org/patterns-travelling/content/imgs_h/Reader.pdf [27.03.2016]

[21] András 2008, p. 12.

[22] Bojana Pejić, The Dialectics of Normality, in: ed. Maria Hlavajova/Jill Winder (eds.), Who if not we should at least try to imagine the future of all this, Amsterdam 2004, pp. 247-270, p. 248.

[23] “Reflective nostalgia has elements of both mourning and melancholia. While its loss is never completely recalled, it has some connection to the loss of the collective frameworks of memory.” Boym 2001, p. 55.

[24] Søren Grammel, Finding the Words, in Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, Vol. 5, Spring/ Summer 2002, pp. 64-77, p. 69.

[25] Grammel 2002, p. 69.

[26] Viktor Misiano, in: Massimiliano Gioni et al. (eds.), Ostalgia, New York 2011, p. 74. Ekaterina Degot, in: ibid., p. 52.; Godfrey 2007, pp. 140-172.; Naomi Hennig et al. (eds.), Spaceship Yugoslavia. The Suspension of Time, Berlin 2011.; Ana Bogdanović, Generation as a framework for historicizing the socialist experience in contemporary art, in: Ulrike Gerhardt et al. (eds.), The Forgotten Pioneer Movement—Guidebook, Hamburg 2014, pp. 24-35.; Ieva Astahovska and Inga Lāce (eds.), Revisiting Footnotes. Footprints of the Recent Past in the Post-Socialist Region, Riga 2015.; Dieter Roelstraete, Field Notes, in: Dieter Roelstraete (ed.), The Way of the Shovel. On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art, Chicago 2013, pp. 14-47.; Maria Hlavajova and Jill Winder (eds.), Who if not we should at least try to imagine the future of all of this?, Amsterdam 2004.; Edit András, The Future is Behind Us: Flashbacks to the Socialist Past, in: Edit András (ed.), Transitland. Video Art from Central and Eastern Europe. 1989-2009, Budapest 2009, pp. 209-221.; Svetlana Boym, Modernities Out of Synch: On the Tactful Art of Anri Sala, in: ibid., pp. 79-91.; Boris Groys, Haunted by Communism, in: Nikos Kotsopoulos (ed.), Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe, London 2010, pp. 18-25.; Zdenka Badovinac, Tamara Soban, Prekinjene zgodovine/Interrupted Histories, Ljubljana 2006.; Svetla Kazalarska, Contemporary Art as Ars Memoriae: Curatorial Strategies for Challenging the Post-Communist Condition, in: Time, Memory, and Cultural Change, Vol. 25, 2009. URL: http://www.iwm.at/publications/5-junior-visiting-fellows-conferences/vol-xxv/contemporary-art-as-ars-memoriae/ [27.03.2016].

[27] Boym 2001, p. 54.

[28] Ibid., p. XVI.

[29] This multi-temporal amalgamation also characterises the futurist opera Victory over the Sun premiered in the Saint Petersburg Lunapark in 1913, one of Steyerl’s possible reference points. Christiane Ketteler, The Futurist Strongman Wants to Become the King of Time in Space, in: Eva Birkenstock et al. (eds.), Anfang Gut. Alles Gut. Actualizations of the Futurist Opera Victory Over the Sun (1913), Bregenz 2012, pp. 278-283, p. 278.

[30] See Steyerl 2015, p. 279.

[31] Boym 2001, p. 347.

[32] The commissar and curator of the German Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale Florian Ebner writes: “Hito Steyerl’s video installation ‘Factory of the Sun’ shows a world in turmoil and a world of images on the move. It involves the translation of real political figures into virtual figures and an innovative experience of making and engaging with images, somewhere between a documentary approach and a full-on virtuality. The new ‘digital light’ is the main medium used to transfer what is left of reality into a circulating digital visual culture.” Florian Ebner, Concept. URL: http://www.deutscher-pavillon.org/2015/en/ [27.03.2016]

[33] Yulia says: “That was a very, very good dying scene. Very nice.” Shortly before the ‘actual’ killing, there are breaking news spreading: “Tests fail—one dead. Protestor is fatally hit—Deutsche denies responsibility./ Speed of light accelerated? Deutsche tests laser drones at Teufelsberg.”

[34] Hito Steyerl (ed.), The Wretched of the Screen, Berlin 2012, pp. 22-24.

[35] Hito Steyerl, In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective, in: eflux, No. 24, April 2011. URL: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/in-free-fall-a-thought-experiment-on-vertical-perspective/ [27.03.2016]

[36] Kerstin Stakemeier, Exchangeables. Aesthetics against Art, in: Texte zur Kunst, No. 98, June 2015, pp. 124-143, p. 134.

[37] One example for the time travel into the future: “My name is Big Boss Hard Facts. I was crushed in the 2018 Singapore uprisings. We occupied the free port art storage and turned it into a render farm cooperative.”

[38] Another example for a superhuman ability: “My name is Naked Normal. I got killed in a protest in London against student fees. When I was born, I could bend light in a Lobachevsky hyberbolic. I can invert light into itself, slow it down until it becomes music.”

[39] Nicolaus Schafhausen, The Future of Memory—Some Thoughts Developed in Advance of the Exhibition, in: Kunsthalle Wien (ed.), The Future of Memory. An Exhibition on the Infinity of the Present, Vienna 2015, pp. 7-11, p. 7.

[40] Mary J. Carruthers (ed.), The Book of Memory. A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture, Cambridge 1990, pp. 20-21.

[41] Cicero, On the Orator: Books 1-2, translated by E. W. Sutton, H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library 348, Cambridge 1942, p. 469.; Carruthers 1990, p. 87.

[42] The change of the exhibition display introduced by the new media art is elaborated in detail in Charlotte Klonk (ed.), Spaces of Experience. Art Gallery Interiors from 1800 to 2000, New Haven & London 2009, pp. 213-223.

[43] Klonk 2009, p. 223.

[44] David Riff, ‘This is Not a Game.’ A Walk through Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun, in: Florian Ebner (ed.), FABRIK, Cologne 2015, pp. 167-193, p. 175.

[45] Boym 2001, p. 354.

[46] Riff 2015, p. 175.

[47] Tom Holert, Spaces of Light. Contemporary Arts, Rooftop Movements, and the Politics of Digital Images, in: Florian Ebner (ed.), FABRIK, Cologne 2015, pp. 23-40, p. 35.