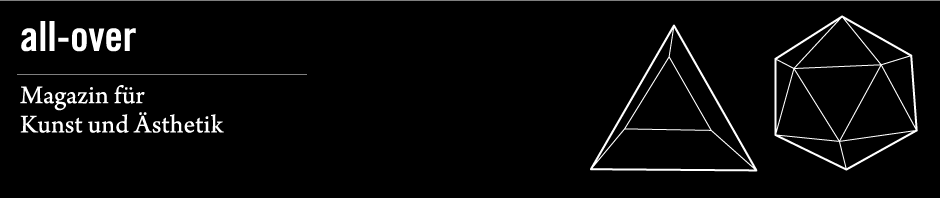

A third and final presentation of Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective is on view in Düsseldorf (4.3–11.6.2017). It concludes a transatlantic voyage that began, manifestly, over a year before, and to the fortieth jubilee of Marcel Broodthaers’s death (1924–1976), at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The exhibition then stationed, grandly, at the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. Now, finally, the works arrive at K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf. One work returns back home at the end of this tour: the Section Publicité of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1972) (Fig. 1). It was mainly thanks to this “publicity section” of Broodthaers’s fictive museum – a key work of the artist, which belongs to the K21 collection – that the institution became a step-partner in this major-players’ collaboration. Since Broodthaers lived in Düsseldorf between 1970 and 1972, the works perform more than an institutional homecoming; yet in comparison with a certain sense of urgency that characterized their making, as institutional property they return “overvalued,” to speak with the artist’s words.[2]

Fig. 1: Marcel Broodthaers, Section Publicité du Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, 1972, detail. Installation with multiple parts, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. Photo: © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, © Kunstsammlung NRW

The works in this exhibition compose, more or less, the same fine selection as in the previous rounds. The sensitivities shift: whereas the condensed MoMA exhibition introduced the artist to a new audience with an explanatory narrative, showing how Broodthaers transformed from poet – into artist – into director of his own fictive museum – and into artist back again (– and finally, through the acquisition of the Daled collection, into MoMA’s assets),[3] the spacious halls of Reina Sofia offered an open playing ground for chance and poetry (successfully applying, perhaps, the formula “disinterest plus admiration,” with which Broodthaers hoped to entice his audience in an open letter from Ostend, 7. September, 1968?).[4] In K21 the installation of the works seems calculated with efficiency.

Again, like in both previous venues (and elsewhere too), the show begins with L’entrée de l’exposition (1974): an environment and at the same time a mini-retrospective that is composed of palm trees, graphical works and photographs.[5] Here, palms that stand in the central atrium announce Broodthaers’s presence in the house, and lead the visitors down the stairs, to the basement, where the exhibition is located. The gesture befits the artist well, time and again he subversively mused with the foundations of the museums that hosted his production, and while living in Düsseldorf he even operated in a basement, at Burgplatz 12, which he transformed into another section of his museum – the Section Cinéma (1972). In the basement of K21, the palm-treed entrance to the exhibition opens to a panorama: at the far back end to the right, one recognizes the greenery of Un Jardin d’Hiver II (1974) that fills the apsis viewing the duck pond outside. To the entrance’s left, in its own blackened room, stands the bright wooden construction of an interior, La Salle Blanch (1975), with black words inscribed on its inner walls. A black booth, the Section Publicité, overpopulated with images of eagles, mirrors it straight ahead, blinking at the viewers with a double eagle slide projection. Black vitrines that contain a selection of Broodthaers’s open letters from 1968 to 1972 stand in between. To their right, on another black painted wall, hang the Industrial Poems (1968-69), combining words and images in plastic plaques. The oeuvre is cleverly laid out in smaller constellations in the pathways. But behind the black wall with its shiny signs hides the true bonanza of this exhibition: a reconstruction, or better, a re-collection of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section XIXe siècle (bis) (1970).

This Section was the first Broodthaers opened in Düsseldorf, and it was already then a “bis” – a French term meaning “encore” in English –, namely of the Section XIXe siècle with which the artist inaugurated the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles on September 27th, 1968, in his home/studio in Brussels. Jürgen Harten, assistant director at the Städtische Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf, was at the time looking for radical artists, and following a recommendation, he visited Broodthaers’s museum in June 1969 (the museum was already running for almost a year, yet Harten was merely about its seventh visitor!). There, Harten would encounter empty art transport crates, a selection of museum postcards on the walls, a slide projection, and the museum director, who showed up late, apologizing politely that he overslept.[6] One could imagine how Broodthaers “showed what he’d done to J. Harten, the assistant of the Städtische Kunsthalle,” and how he said: “But it is art […] and I will willingly exhibit all of it.”[7] Harten immediately offered the artist to exhibit his museum in the revolutionary Between series, taking place at the Kunsthalle between one programmed exhibition to the next. Broodthaers would only agree to the proposal, on the condition that instead of showing empty crates, he would be able to use the operation of the hosting institution to loan real works of art for his demonstration. “Agreed,” replied the museum’s director and the assistant director.[8] And so, following an official opening speech by Harten, between February 14th and 15th, 1970, for two days only, eight nineteenth-century paintings from the Düsseldorf Municipal Art Museum hung at the Kunsthalle, in the framework of a fictive museum that conquered a real one.[9]

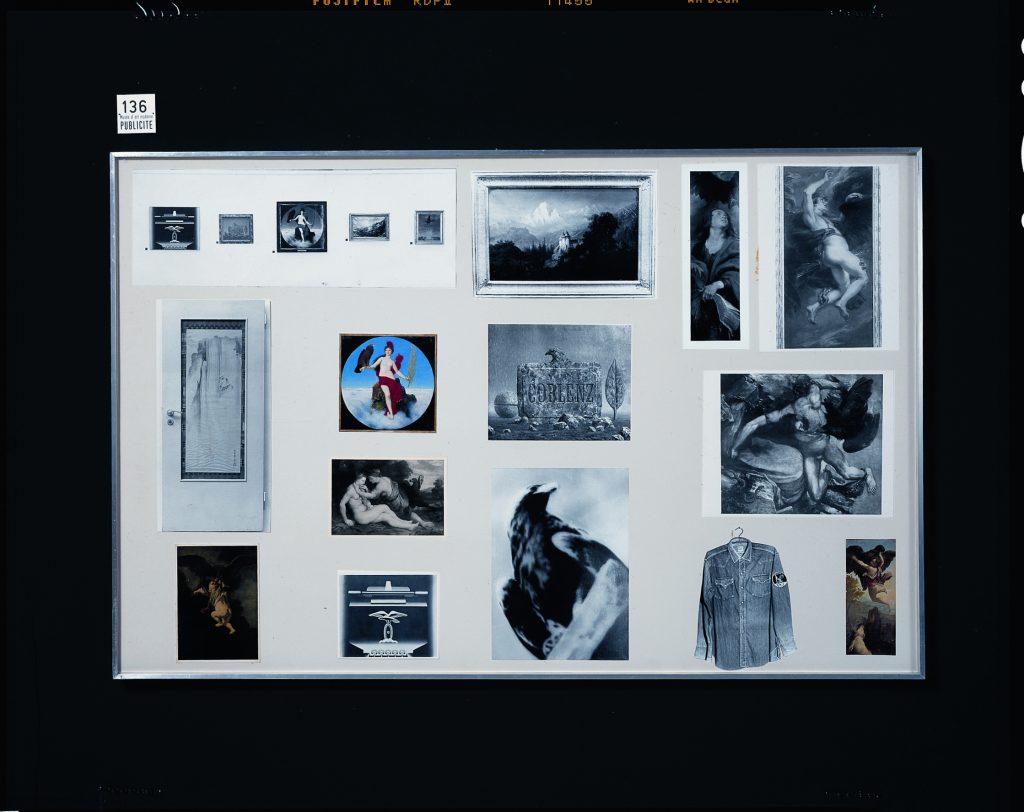

The current “encore” of the “(bis)” in K21 comprises: a poster of this section, featuring the four caryatides representing the visual arts that (still) stand near the Kunsthalle; several copies of two posters with images of crates, advertising the museum’s Section XIXe siècle (September 1968 – September 1969, Brussels) and Section XVIIe siècle (September 27th – October 4th, 1969, Antwerp), hanging above the visitors’ heads; documentary photographs from those previous sections of the museum; a film – Un Discussion Inaugural (1968) – and a continuous projection of images of nineteenth-century paintings and caricatures; wall inscriptions that read “DOKUMENTATION / INFORMATION” and “MUSEE D’ART MODERNE / XIXe SIECLE (BIS) / DEPARTEMENT DES AIGLES”; and the same eight nineteenth-century paintings from the art museum (today called Museum Kunstpalast), arranged in a grid according to size and genre (Fig. 2). To these the curator Doris Krystof – who took up the challenge of re-presenting this work for the first time since 1970 – supplemented a grey carpet, mimicking the Kunsthalle as it appears in documentary photographs of this event, which are also present in a black vitrine in the room, and a black museum’s leather bench.

Fig. 2: Installation view Marcel Broodthaers: Eine Retrospektive, 2017, K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf.Photo: © Achim Kukulies, Düsseldorf, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017.

This is truly a bonanza, not because it is real gold – which is elsewhere to be found in the exhibition, by the museum’s Section Financière that in 1971 offered a gold ingot with the eagle emblem for sale, for a price fixed in relation to the gold’s value: namely, double. This is truly a bonanza because the “encore” of the “(bis)” is rather unconvincing. The first “(bis)” at the Kunsthalle was questionable to begin with, showing paintings that are quite mediocre (in the retrospective’s opening, Manuel Borja-Villel spoke about the improbable possibility of showing this work at MoMA with paintings from the Metropolitan, or in Madrid with paintings from Prado). Furthermore, the current “encore” is an unconvincing imitation of the previous, by now iconic “(bis)”, since the room is too small, and an architectonic pillar divides it further in two. Finally, if one endeavoured to truly reconstruct the work, one could do it at the Kunsthalle directly, in situ (for two days only? or longer?). But it is exactly because of these deviations that this imitation, copy, or false re-presentation, reveals something real.

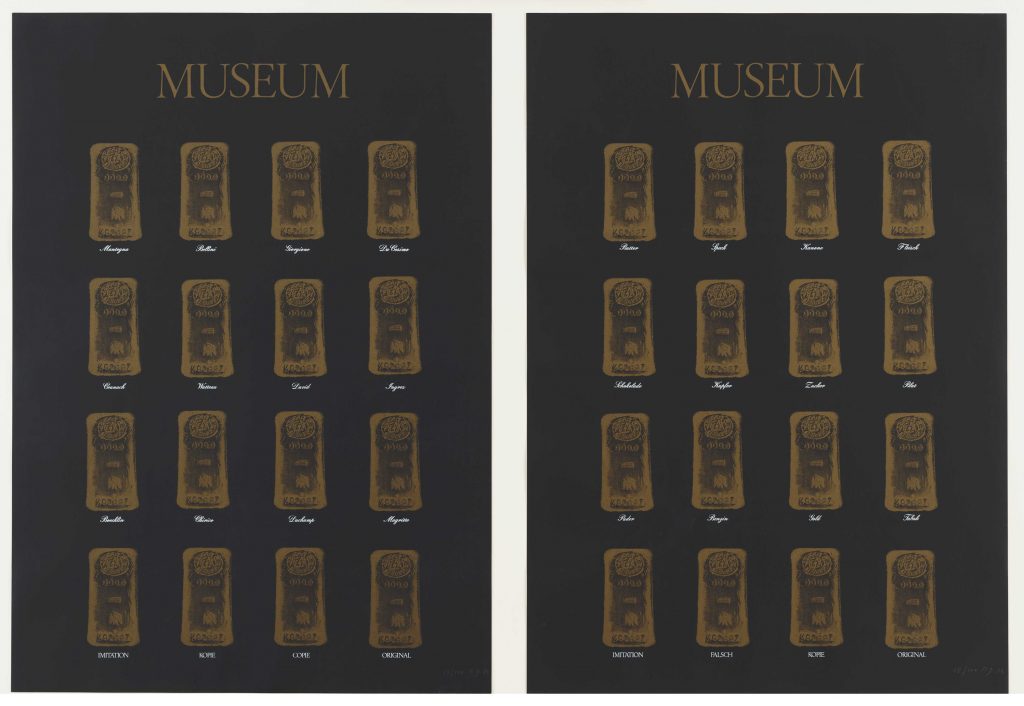

I am thinking here of the double screenprint Museum-Museum (1972) that hangs in L’entrée de l’exposition: in its two parts, the word “MUSEUM” titles images of the eagle-marked gold ingot, which are lined four by four, and under each appears an inscription (Fig. 3). The last row reads: “IMITATION”, “KOPIE”, “COPIE”, “ORIGINAL” in the left part, and in the right: “IMITATION”, “FALSCH”, “KOPIE”, “ORIGINAL”. Broodthaers questions the relations between the museum and the value of the objects it conserves. What could his fictive museum guarantee, doing business with an eagle mark and gold ingots? What is the status of Broodthaers’s Musée: a museum’s imitation that maintains copies, a fake museum, yet an original work of art? What happens when a real institution exhibits a fictive museum, as the Kunsthalle did in 1970 and in 1972? Could a museum exhibit the “original” Musée today, or is every attempt doomed to failure, (re)producing nothing but an imitation, a copy, or a fake?

Fig. 3: Marcel Broodthaers, Museum-Museum, 1972, two screenprints, each 83 x 59.1 cm; publisher: Edition Staeck, Heidelberg; printer: Gerhard Steidl, Göttingen; edition of 100, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Associates Fund, 1991. ©The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers c/o SABAM Belgium – VEGAP 2016

For those of us who now experience the museum for the first time (and most of us do – but do we?), this Section represents (once again), a key to its own critique. With every click of the continuous slide projection, and with the altering sequences in the film that runs beside it, this Section unlocks the relations of the artwork and the museum. The film shows, among other fragments, Broodthaers smoking while pacing back and forth in the garden of his Musée (one recognizes the inscription “DEPARTEMENT DES AIGLES” on the brick wall behind him). A cut replaces this scene with a close-up of a girl’s face. It then returns to Broodthaers, and alternates back to the girl, for a few times, before continuing with other fragments. In the neighbouring slides, images rotate between nineteenth-century paintings and caricatures. Most paintings are Ingres’s, showing naked women in erotic poses. Sometimes Broodthaers inverts the image, and in the negative the voyeuristic paintings expose black bodies. The caricatures are pear-faces by Grandville. Compared to the subversive transformations from man to fruit that the caricatures suggest, high art seems bluntly pornographic: white flesh may turn black by a trick, yet the painted bodies remain nothing but bare sex commodities on display. The paintings that hang on the wall strengthen this impression, with some female nudes or semi-nudes in mythological themes. The unease that the pornographic in art evokes, extends to a sense of fetishism that the painted representations unveil: of landscapes, in aestheticized romantic depictions; of farm animals, in naturalist studies that take their bodies apart; of portraits, in the sought-after authoritative likeness; and of death, the physical allure of which a human skull embodies. The cultural-ideological fetish in the artworks expands into the materialist cult of the artworks, into the lust for the original artwork itself.

Joseph Beuys adds magic and politics into this cult, or this is what Broodthaers reproaches him for, in another Düsseldorf episode. In a famous open letter Broodthaers addresses to Beuys in 1972, Broodthaers “copies” a letter from Jacques Offenbach to Richard Wagner, which Broodthaers allegedly “found” in an attic in Cologne.[10] Broodthaers thus identifies Beuys with Wagner and himself with Offenbach. Now, in Broodthaers’s retrospective, we find another message from Broodthaers-Offenbach, this time in a basement in Düsseldorf, where we can further identify him with Grandville. Walter Benjamin suggests that commodity fetishism is the secret theme of Grandville’s art.[11] Broodthaers’s is cultural fetishism. He shows us further, how, as Grandville’s faces transform into pears and vice versa, pornographic art becomes cultural capital, and cultural capital becomes objectified fetish. Broodthaers’s mussels and eggs works are already covered with a patina, MoMAfied, “overvalued.” His museum escapes this fate: when every attempt to put the fictive Musée on display is real, it could not but results in a failed imitation, a copy, a fake. And so, as Grandville’s faces of authority turn into pears, the Musée pears away.

“Museum. enfants non admis” says an Industrial Poem on the other side of the wall: “Museum. children not admitted.” Is it because of the porn, that the young girl from the film should stay out of the museum, in which Broodthaers paces back and forth, smoking, so restlessly? Or, perhaps, born too late to enter Broodthaers’s “original” Musée, today’s children can now only admit a caricature – Again? Encore!

[1] The title adds two variations to the sentences Marcel Broodthaers states in a series of literary paintings, Série en langue française (Série de neuf peinture sur un sujet littéraire) (Series in the French Language [Series of nine paintings on a literary subject]) (1972), which read “PAUL VALERY FUME” (Paul Valery smokes), “RENE MAGRITTE ECRIT” (René Magritte writes), and so on. The paintings are shown in the Broodthaers retrospective in K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen Düsseldorf, and are also reproduced in the comprehensive catalogue accompanying the exhibition, Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective (cat.), New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2016, p. 275.

[2] See Broodthaers’s open letter from Paris, 29. November 1968, reproduced in Ibid., p. 180. See also the quotation in note 6.

[3] Herman and Nicole Daled, Broodthaers’s friends and collaborators, were enthusiastic supporters of Conceptual Art throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 2011 MoMA acquired their collection, on which this retrospective noticeably relies.

[4] “We trust that the slogan ‘disinterest plus admiration’ will entice you,” Broodthaers writes concerning the planned opening of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles. See Broodthaers’s open letter from Ostend, 7. September 1968, reproduced and translated in Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective, p. 228.

[5] The work opened the Broodthaers retrospective at Fridericianum in Kassel in summer 2015 as well, which I reviewed here: “No Tricks, no Scams. Marcel Broodthaers at the Fridericianum, Kassel,” Tohu Magazine (December 2015).

[6] Broodthaers lists the components of the museum in the open letter from Paris, 29. November 1968, as follows: Thanks to the support of a shipping company and of a few friends, we have been able to set up this department, which comprises in principle order: 1/ crates 2/ postcards “overvalued” 3/ a continuous projection of images (to be continued) 4/ a devoted staff Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective, p. 180, translation revised.

[7] I here adapt the often-cited confession on the invitation to Broodthaers’s first solo show: I, too, wondered whether I could not sell something and succeed in life. For some time I have been good for nothing. I am forty years old … / Finally the idea of inventing something insincere crossed my mind and I set to work straightaway. At the end of three months I showed what I had produced to Ph. Edouard Toussaint, the owner of the Galerie Saint Laurent. / But it is art, he said/ And I will willingly exhibit all of it / Agreed, I replied. If I sell something, he takes 30%. / It seems these are the usual conditions, some galleries take 75%. / What is it? In fact, objects. See reproduction and translation in Ibid., pp. 80-81.

[8] See note 7.

[9] For a most valuable detailed account of the events at first hand, see Jürgen Harten, Marcel Broodthaers. Projet pour un traité de toutes les figures en trois parties. An Attempt to Retell the Story, Cologne: Walther König, 2015.

[10] See Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective, p. 264.

[11] See Walter Benjamin, “Exposé of 1935,” The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 7.