You walk down Reina Sofia’s long stone arcade. It encircles a sunny green court garden, which tempts you by its seductive grand windowpanes to relax in the calm and protected interior exterior. But, you are headed towards the palm trees lining the end of that corridor. You arrive at the entrance of the retrospective. Under a potted palm tree you face a black and white picture of Marcel Broodthaers, in which the artist is wearing a bowler hat. Entering the exhibition, you find yourself between even more palm trees, inside of a winter garden.

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016. Photography: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

This is L’Entrée de l’exposition (The Entrance to the Exhibition, 1974), a work that became a classic exposition for a Broodthaers retrospective. It emerged as a mini auto-retrospective on its own right in 1974 at Brussels’ Palais des Beaux-Arts: with a picture that bears the letter “a”, photographs, and printed editions that hang on the walls. Classic is also the prologue of “Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective” at Reina Sofia, which begins in the following room with a display of his pre-artistic journalistic, photographic and poetic works. A projection of the first 16 mm film La Clef de l’horloge: Poème cinématographique en l’honneur de Kurt Schwitters (The Key of the Clock: A Cinematographic Poem in the Honor of Kurt Schwitters, 1957) is in the next room, situated by early assemblages made of plaster, eggs, plastic balls and air pipes. Two wooden vitrines with collected objects from different moments in Broodthaers’ production hint toward what is to come. The board is now set, and so the game begins.

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016. Photography: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

It brings to mind a German children’s game called “Ich packe meinen Koffer,” or – I pack my suitcase, and:

- I take eggs.

- I take eggs, and a rose.

- I take eggs, a rose, and a table.

- I take eggs, a rose, a table, and a suitcase.

- I take eggs, a rose, a table, a suitcase, and – a bone … !

Marcel Broodthaers, Fémur d’homme belge, 1964-1965, 8 x 47 x 10 cm, Collection Sylvio Perlstein, Antwerp. Image courtesy Maria Gilissen Archives of Marcel Broodthaers. (c) The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers c/o SABAM Belgium – VEGAP 2016

As the visitor packs her suitcase, the scholar unpacks her library, and with every object she lays her eyes on, she rediscovers a world order anew. To further paraphrase Walter Benjamin and his confession “Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” we join the exhibition’s piles of objects, some of which are once again seeing the light of museum after several “years of darkness,” so that we “may be ready to share … a bit of a special mood – it is certainly not an elegiac mood but, rather, one of anticipation.”[1]

- I take the signature

Throughout the exhibition the viewer encounters motives, images, figures and works that she may encounter again in a later room – a chance rendezvous. Thus, the unfolding relations between the works are neither reduced to linear progression nor to strict chronological succession. The initials “M.B.”, for example, emerge first in the printed edition: Gedicht – Poem – Poème / Change – Exchange – Wechsel (1973). It seems to weigh the poetic and monetary value of the signature, and is an integral part of l’Entrée de l’exposition. In the course of the exhibition the, by now, iconic initials return suggestively as an unlimited edition in the print La Signature. Série I. Tirage illimité (The Signature. 1st series. Unlimited edition, 1969), in which the signature repeats ad absurdum. Finally, in the film Une Seconde d’Éternité (D’après une idée de Charles Baudelaire) (A Second of Eternity, After an Idea of Charles Baudelaire, 1970), the initials reemerge, as they were being signed over and over again, in an animated sequence of 24 frames that comprises “a second of eternity.”

- I take Veritablement

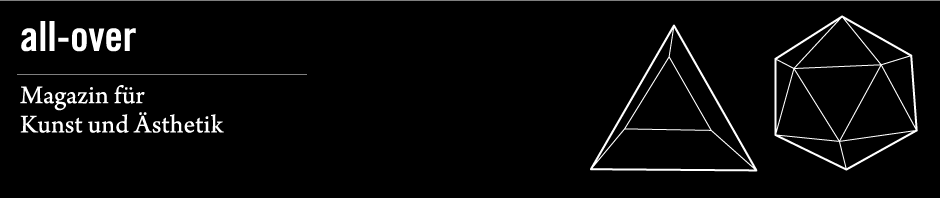

This continuous recurrence of signs and figures haunts the spectator. Notably, the approach that Manuel Borja-Villel and Christophe Cherix apply to curating this exhibition follows a strategy the artist implemented already in his own practice: Broodthaers often reused his pieces as readymade material for future productions. He represented an object by image, repeated an image in film, related a film to a publication, and, most famously, recruited a publication and transformed it into an object. The curators effectively demonstrate this correlative principle in a condensed room dedicated to Court-Circuit (Short-Circuit), Broodthaers’ 1967 solo exhibition at Brussels’ Palais des Beaux-Arts. Next to varying components, a shovel with coal rests on a pedestal placed in front of six photographic canvases bearing its image, and the word “Veritablement” – meaning “truly” – echoes throughout the photographic canvases hanging parallel from each other in the room. One of those pictures reappears on the back cover of Court-Circuit’s catalogue, which is also displayed in the vitrine close by.[2] For Broodthaers, exhibitions supplied readymade material for catalogues. His catalogues do not merely document the exhibitions but augment them, until it becomes difficult to distinguish ergon from parergon.[3] Fortunately, the curators don’t overlook this aspect of the artist’s production: here all kinds of exhibition-related materials, such as invitation cards, exhibitions brochures, and catalogues, are scattered throughout the exhibition space.[4]

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016. Photography: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

- I take La Fontaine

Within this overflow, the exhibition is not playing the card of reckless confusion. Broodthaers’ ensembles are installed sensitively in composed groups, as is the case with Le Corbeau et le Renard (The Raven and the Fox, 1967-68) – a film projected onto a special screen with printed words that may refer back to La Fontaine’s fable. Originally, this film was sold in an edition that included two screens and additional photographic canvases. At Reina Sofia all the objects – screens, film reels, prints – are presented together in one room. Yet groups of works, like Le Corbeau et le Renard, are not cast in marble; here they do not assert a claim for historical irrevocability. Instead, they are exhibited as ensembles, recurring but being loosely connected with works from other sections of the exhibition. Toward its end we re-encounter a work related to Le Corbeau et le Renard, in which the doubled image of Broodthaers in the act of writing the fable reappears: Pour un art d’écriture. Pour une écriture de l’art (On the Art of Writing. On the Writing of Art, 1968) hangs in a room that contains objects from L’Angelus de Daumier (The Angelus of Daumier, 1975) – one of Broodthaers’ last six exhibitions that he announced as “retrospectives.” In view of the artist’s self-curated auto-retrospectives, the task of curating today a posthumous (re-)retrospective becomes even more complicated.

- I take the dice

As a format, a retrospective exhibition re-collects into the space of a single institute dispersed works produced in different places and under different circumstances. The passing of time drifts them further apart: some become especially difficult to approach. Such is the case with the multi-sectioned transitory Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, 1968-1972). Others are carried overseas by the market. For example, the collection of Herman Daled, Broodthaers’ friend and collaborator in Brussels, arrived at MoMA in New York. MoMA was also the first station for this world-travelling exhibition that eventually concludes its transatlantic voyage during spring 2017 at Stiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf. It seems that now, with the fortieth anniversary of his untimely death in 1976, Broodthaers is having his “moment.”[5] Within this commemorating atmosphere, it is worth noting that unlike previous attempts to exhibit Broodthaers’ oeuvre, this retrospective at Reina Sofia escapes the trap of a simplified and heroic historical narrative.

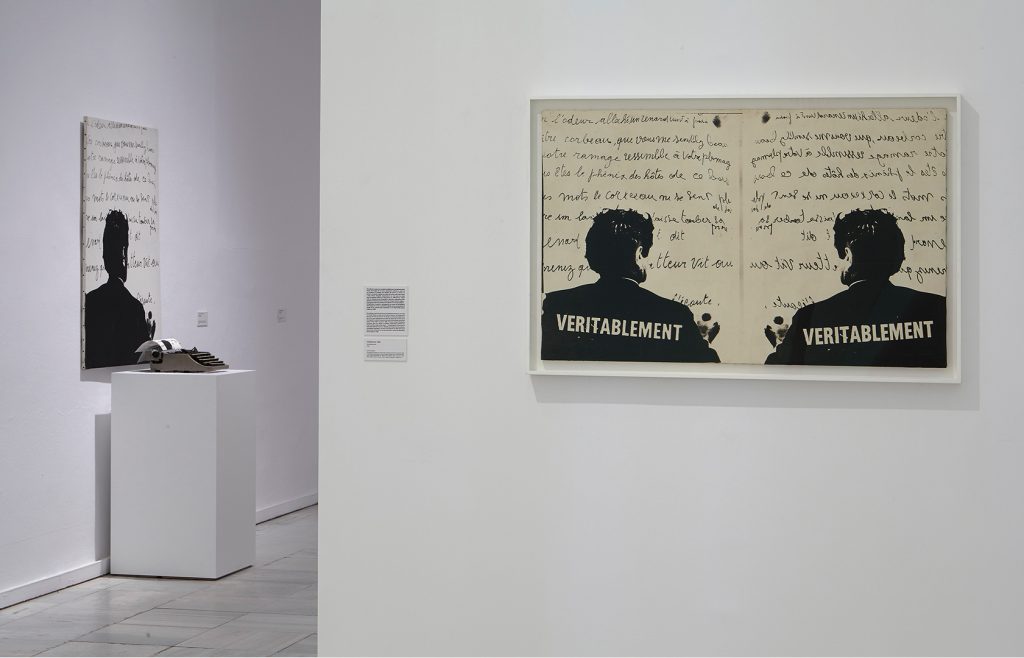

Marcel Broodthaers, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, 1969, artist’s book, offset lithograph on transparent paper, page: 32.4 x 24.9 cm; publisher: Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp; Galerie Michael Werner, Cologne; printer: Vermin, Antwerp; edition of 90; The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Howard B. Johnson in honor of Riva Castleman, 1994. (c) The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers c/o SABAM Belgium – VEGAP 2016

It seems to deliberately follow poetic threads instead. When it comes to presenting the work of an artist who is as deeply engaged with poetry as Broodthaers, this is of course an achievement. Yet it isn’t the illustration of his poetry that makes the exhibition poetic. Just as Broodthaers’ take on Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard is not an illustration – but an Image. Passing through the room devoted to his 1969 Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé (Literary Exhibition on Mallarmé) at the Antwerp Wide White Space Gallery, and viewing the artist’s book and aluminum plates where Mallarmé’s verses turn into black bars, conjures the critical potential of a voyage between words distributed on paper. Broodthaers’ works are similarly dispersed throughout the wide white spaces of the museum, and the spectator becomes a captain who navigates her way through the artist’s playful enigmas.

- I take a red seat

Throughout the exhibition, the alert spectator-navigator can discover a range of visual alignments. Precisely set up, they do not merely direct the visitor’s view, but also establish communication between works. It is virtually halfway that one quietly recognizes the distinctive background piano music of Un Jardin d’Hiver II (A Winter Garden II, 1974). With every step further, the music is becoming louder. After traversing the fictitious Musée d’Art Moderne, and entering a room of films and images that refer to or are allegedly created by Charles Baudelaire, one can finally spot palm branches again. The interlocking relationships developing ever since the exhibition’s beginning demand a break: remarkably – and the preoccupied voyager will most certainly only now realize – there are hardly any accommodations for sitting within this exceptionally comprehensive exhibition. Therefore the red chairs in the winter garden come as a welcomed opportunity to rest and watch passersby. (The experienced Broodthaersian will quickly ascertain whether she is really allowed to sit, and will happily learn: yes, please, take a seat!) Yet the calm chill-out-atmosphere promotes a certain indisposition. The aestheticized relaxation begins to unravel its multilayered deception and you discover yourself sitting in an elitist western, all-white cube, in the midst of the relics from the colonial era.

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016. Photography: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

- I take nothingness

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016.

The curatorial decision to limit the resting spots to a few crucial points – mostly seats already arranged in Broodthaers’ conception of the works – strains the intense effect of this retrospective. While sitting between the exotic trees on a red chair and recovering from the ongoing play, a view into La Salle Blanche (The White Room, 1975) opens up. This wooden, partly white painted reconstruction of Broodthaers’ work and living space is adorned with various art-world related words in black, and is installed in a black-painted room. The confrontation comes as a severe shock: is this a mausoleum? The stage-like model of the apartment on the Rue de la Pépinière, where Broodthaers inaugurated the first section of his Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, seems to be entombed here, and the literal sense of posthumous becomes apparently urgent. One faces nothingness, as Jean-François Chevrier pointedly stated.[6] But you don’t get a break for the work of mourning. The game must go on.

- I take a cannon

Subsequent to the laid out La Salle Blanche and the quasi-recovering room of Un Jardin d’Hiver, the next room catches you off-guard: we find ourselves standing in Décor – A Conquest by Marcel Broodthaers (1975), his renown retrospective at the ICA London. Although this installation – as it is labeled today – was originally conceived as a film set, at Reina Sofia the visitor cannot decide whether she wants to step on the stage or not. To continue the exhibition, the visitor must proceed through the two-room installation, beginning with the 19th-century room. She enters from backstage, from behind two cannons. Amid the museum’s faux-historic ensemble of furniture and objects, positioning supposedly noble chairs on Astroturf, we might ask ourselves: are we the actors, playing around just like the two fake crabs in the vitrine at the corner of the room? The curatorial reinstallation heats up the political implications embedded in Décor, an interesting choice that definitely calls upon us for testing. Part two of Décor, the 20th-century room, awaits the spectator with rifles arranged in a glass cabinet on the wall, and a more or less welcoming white plastic table set of four white chairs with striped cushions that match with the sunshade. Unmistakably, this is a model for the petty bourgeois terrace. An unfinished puzzle depicting the battle of Waterloo is strewn on the table. The red chair turns into a white one, which leads to a new question: are we to sit here and complete the puzzle? We would rather leave these seats for someone else but as visitors from the 21st-century, these are seats we inherit.

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016. Photography: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

- I take a message

Considering Décor as a film set in the first place, it is regrettable that the film – La Bataille de Waterloo (The Battle of Waterloo, 1975), which Broodthaers shot in this décor, is not on view. This is one of the very few “missing links” of the retrospective. On the other hand, the reconstruction of the DTH exhibition, which was presented in 1970 at the MTL gallery in Brussels, is as impressive for being ambitiously meticulous as it is confusing. It includes a reconstruction of the gallery’s window, which was covered with inscriptions and upon which a film was projected during the last day of the MTL show. And so the visitor may view the film from outside of the gallery from within the museum, or, from within the gallery embedded into this retrospective. Finally, the retrospective concludes with another rare opportunity to view the film Figures of Wax (Jeremy Bentham) (1974). It projects onto the only white wall in a room covered with dark-brown wooden cabinets. Is this another reconstruction, mimicking the wooden cabinet that encloses the auto-icon of Jeremy Bentham that appears within the film? You first wonder. It turns out to be Reina Sofia’s “protocol room,” a befitting setting for the film in which Broodthaers gives the dead philosopher an opportunity to “make a statement,” share “a secret,” “or a special message.”[7]

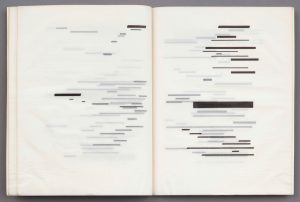

Marcel Broodthaers, Museum-Museum, 1972, two screenprints, each 83 x 59.1 cm; publisher: Edition Staeck, Heidelberg; printer: Gerhard Steidl, Göttingen; edition of 100, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Associates Fund, 1991. (c) The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers c/o SABAM Belgium – VEGAP 2016

You leave the exhibition and find yourself, overwhelmed, a little disoriented, back in a long stone arcade – somewhat confused too, after confronting a barrage of imitations, copies, originals, fakes. These are all essential to the museum, according to the printed edition Museum-Museum (1972), another part of L’Entrée de l’Exposition with which we started our journey in what seems to be centuries ago. The curators carried out Broodthaers’ striking conquest of space, achieved through a sensitive reading of Mallarmé, whom Broodthaers sees as “the founder of contemporary art. ‘A throw of the Dice will never abolish chance.’”[8] And as the throw of the dice repeats, indefinitely, the game continues:

- I take a palm tree, I take a palm tree, I take a palm tree …

[1] Walter Benjamin, Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Book Collecting, in: Hannah Arendt (ed.), Illuminations, New York 2007, p. 59.

[2] Another picture is the eye-catching cover image of the comprehensive catalogue accompanying this retrospective.

[3] On ergon and parergon, and the problem of distinguishing between what is interior to a work and what is exterior to it, see Jacques Derrida, The Parergon, in: October, No. 9, Summer 1979, p. 3–41, especially p. 24–26.

[4] Here at Reina Sofia, as opposed to MoMA, New York, the first stop of this travelling exhibition. At MoMA the printed matter was mostly absent, as Trevor Stark rightly observes. See Trevor Stark, Marcel Broodthaers, Art Historian’s Artist, in: Texte zur Kunst, No. 103, September 2016: p. 227–232.

[5] See: The Moment of Marcel Broodthaers? A Conversation, in: October, No. 155, Winter 2016: 111–150. A roundtable-conversation with Benjamin Buchloh, Borja-Villel, Cherix, Stark, Rachel Haidu and Rosalind Krauss, published on the occasion of the retrospective.

[6] In the panel discussion “Encounter centered on Marcel Broodthaers. What happened to institutional critique?” with Borja-Villel, Cherix, Jean-François Chevrier and Dirk Snauwaert, Sabatini Building, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia Madrid, 5. 10. 2016.

[7] Marcel Broodthaers interviewing Jeremy Bentham in his film “Figures of Wax” (1974), for a full transcript see: Wilfried Dickhoff, Marcel Broodthaers: Interviews & Dialoge 1946–1976. Kunst Heute Nr. 12, Köln 1994, S. 140.

[8] Marcel Broodthaers, Statement by the Artist, in: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (ed.): Amsterdam, Paris, Düsseldorf, New York 1972, n.p.