-

Aktuelle Ausgabe

Current IssueSebastian Mühl

Moderne im Archiv

Zur Kritik des utopischen Erbes in der GegenwartskunstSophie Publig

Shifting Perspectives

Beau Dick‘s Multi-Layered Strategy of Agency on documenta 14Thomas Helbig

Die Gegenwart des Historischen in Christian Petzolds TransitLotte Beckwé, Bernard Coppens and Isi Fiszman

To tell the truth

Artist tourism and storytelling in and about WaterlooSteyn Bergs

Institutional Transpositions

Two Music Exhibitions and the Politics of AttentionStefanie Heinzl

Verssuche

Eine typographische Lektüre des Coup de Dés von Stéphane Mallarmé

The Puppy Factory

Posted in Ausgabe 11, Bildstrecke

Comments Off on The Puppy Factory

Ausgabe #11

Getting ready for 2000 AD – an imperative that sounds anachronistic today, sixteen years after the millennial turn (and 984 years before the next one) – functioned as a title for Benjamin Patterson’s first solo exhibition back in 1992 and suggested to the audience to brace themselves for what was to come. In order to achieve this, the Fluxus artist vowed to „DO MORE“ in his publication for the show, and – as Julia Elizabeth Neal argues in this issue – effectively created a starting point for much his future work with a compelling self-interview that he continued to come back to until recently.

Johanna Braun, no less thinking ahead, talked to UCLA professor Laure Murat about opening up academic discourse towards a wider audience; an issue connected to her own biography as a Quereinsteigerin to academic teaching. More rooted in the present and with a glance oversees they further discuss the topic of madness – a subject to a recent publication by Murat.

Back in Europe, Dominik Reisinger takes a close look at the Bankgebäude am Floridsdorfer Spitz in Vienna, discussing the architects’ way to encounter the challenges of constructing in existing contexts. As Reisinger argues, the architects found a solution by confronting the original style with its architectural countermovement to fulfil present needs, thus creating a symbiotic relationship of two different building traditions, hence a “Wiener Melange”.

Hannah M. Bruckmüller and Michal B. Ron, both graduates working on the artist, have visited “Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective”, currently on view at the Reina Sofia in Madrid. In their review for all-over they unpack their theoretic suitcases in order to reexamine, by playful means, the numerous objects and installations that the artist orchestrated in a complex, yet ludic, net of interconnections and reiterations.

Again, temporality is a decisive axiom in Oliver Caraco’s review of the book “Kunstgeschichtlichkeit. Historizität und Anachronie in der Gegenwartskunst,” edited by Eva Kernbauer, which takes Rancière’s concept of anachronism as a starting point to highlight a recently rather common tendency in contemporary art. The use of history and historicity of art as subject and potentially critical tool in art practice is explored from different angles but eventually it might not suffice to break the hierarchies of the art world that, as Caraco maintains, are nonetheless dominated by the market.

As we too are getting ready to face a (politically) uncertain future, we will continue our mission to bring you high quality articles and wish you: Bonne lecture!

Hannah Bruckmüller | Jürgen Buchinger | Barbara Reisinger | Stefanie Reisinger

Posted in Ausgabe 11, Editorial

Comments Off on Ausgabe #11

Heterogenität einer global(isiert)en Kunst?

Eva Kernbauer (Hg.), Kunstgeschichtlichkeit. Historizität und Anachronie in der Gegenwartskunst, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, München 2015.

Dass Geschichte einen wichtigen thematischen Gegenstand gegenwärtiger künstlerischer Auseinandersetzung darstellt, wurde unlängst wiederholt festgestellt.[1] Der vorliegende Tagungsband hat es sich nun zum Ziel gesetzt, der Beschäftigung zeitgenössischer Kunst mit der Kunstgeschichte nachzugehen, wozu der Neologismus der „Kunstgeschichtlichkeit“ geprägt wird. Einmal mehr dient dieser Kontext auch der Frage nach dem Zeitgenössischen zeitgenössischer Kunst, die, wie gezeigt wird, auf vielfältige Weise mit der nach ihrer Geschichte im Dialog steht.

Den Auftakt zum Band bildet die deutsche Erstübersetzung von Jacques Rancières Der Begriff des Anachronismus und die Wahrheit des Historikers. Rancière skizziert hier in seiner üblichen destruktiven Methode eine kritische Genealogie der Geschichtswissenschaft. Im Ausgang von Platons Unterteilung der Welt in Sein und Werden, und das heißt in Wissen(de) und Glauben(de), bildet die Geschichtswissenschaft einen positivistischen Wahrheitsbegriff aus, dem als größte Sünde der Anachronismus gilt. In Folge einer zunehmenden Rationalisierung des Faches im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert wird mit diesem Begriff schließlich ein Wahrheitsregime als „Über-Gegenwart“ etabliert, welches ein Ähnlichsein mit der Zeit, eine Ko-Präsenz der Gegenwart, verordnet: Es wird so eine Beziehung von Wahrheit und Zeit eingerichtet, die von GeschichtsadvokatInnen mit poetischen und rhetorischen Mitteln verteidigt wird. Den Begriff des Anachronischen führt Rancière als emanzipatorische Auflehnung gegen dieses Zeitregime ein: Gerade im Verlassen der ideologisch homogenisierten Zeit, die das Mögliche vom Unmöglichen trennt, sieht er das Potenzial wie auch die Bedingung dafür, Sprünge zu vollziehen, Geschichte zu machen. Maria Muhle argumentiert daran anschließend mit „Aufteilung der Zeiten“ – Die Anachronie der Geschichte dafür, dass Rancières Auffassung der Zeit grundlegend für sein Theorem der „Aufteilung des Sinnlichen“ ist. Politik, also die „polizeiliche Ordnung“ von „Orten und Rollen“, von „Anteilen am Gemeinsamen“, ist historisch gewachsen, wird aber vom Wahrheitsregime der Zeit fixiert und ist demnach eine Verräumlichung des Zeitlichen. Wie Politik vollzieht sich Geschichte als Unterbrechung der „harmonischen“ Aufteilung des Sinnlichen.

Eric C. H. de Bruyn interpretiert in diesem Sinne in Das holografische Fenster und andere reale Anachronismen die Holografie als dystopische Verwirklichung des Posthistorischen, aus dem alles Anachronische gelöscht ist. Wenn nach Panofsky durch das fensterförmige perspektivische Bildmodell Distanz zur Welt, auch eine intellektuelle Entfernung der Gegenwart zur Vergangenheit, ein geschichtliches Bewusstsein, etabliert wird, so hebt das „holografische Fenster“ diese Distanz auf. In diese Richtung wirken neue, so genannte instrumentelle Bilder, etwa 3D-Brillen oder per 3D-Scanner generierte Modelle: Der perspektivische Rahmen wird gelöscht und das Bild zum Modell der Wirklichkeit. Ähnliches geschieht, so de Bruyn mit Paolo Virno, in der postfordistischen Zeit, wenn das je historisch bedingte Vermögen, das als formaler Anachronismus immer in Differenz zum aktualen Tun steht, verdinglicht wird: In dieser Rückkoppelung des Vermögens an die Wirklichkeit entsteht ein realer Anachronismus, in welchem wir „alle zu Epigon_innen […] unseres eigenen zukünftigen Potentials werden.“ Es geht schließlich um Strategien, die dieser posthistorischen Zeit entgegenarbeiten. Etwa die Herausstellung der Eigengeschichtlichkeit von Dingen, wie Hito Steyerl sie in „In Free Fall“, der „Biografie eines Objektes“, vollzieht. In einer solchen „Sprache der Dinge“ entzieht sich das Objekt der „holografischen Glocke“, weil es zum aktiven Handlungsträger wird, dem somit das Potenzial zukommen könnte, die gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse zu ändern. Antonia von Schönings Archäologie der Zukunft. Zum Entwurf von Geschichtlichkeit in Walid Raads „Scratching on Things I Could Disavow – A History of Art in the Arab World“ fordert in ähnlichem Sinne die Generierung eines Abstands zur Gegenwart, den sie in Walid Raads Arbeit verwirklicht sieht. Ein von ihm in poetischen Transformationen etablierter „therapeutischer Abstand“ zur Hegemonie der westlichen Moderne ermöglicht eine Optik, die etwa der zeitgenössischen arabischen Kunst Spielraum gibt. Auch sieht David Joselit in Über Aggregatoren eine drohende Blendung durch die „spektakuläre Unmittelbarkeit“ in der zeitgenössischen Kunst, die globale Ungleichheiten und Ungleichzeitigkeiten verdeckt. Als Gegengift fordert er die Etablierung eines „internationalen Stils“, wo in sogenannten Aggregatoren unter einem gemeinsamen Stilbegriff verschiedene „lokale Dialekte“ versammelt werden können. Joselit wendet sich damit speziell auch gegen einen avantgardistischen Fortschrittsglauben, der sich als konstanter Bruch versteht. In diesen Aggregatoren könnten sich Kollektive, die ihre Heterogenität und Asynchronität beibehalten, bilden. Helmut Draxler entwickelt in Jenseits des Augenblicks: Geschichte, Kritik und Kunst der Gegenwart eine Art ontologische Strukturbestimmung eines solchen kritischen Abstandes. Eine historische Aufarbeitung der Kategorie Gegenwart, die sich als Vermittlung von Vergangenheit und Zukunft zeigt, führt Draxler zu deren Konzeption als Riss. In diesen Riss „nistet“ sich – als eine Abgrenzungsbewegung gegen Tradition – die Kritik ein, der die Form der Behauptung zukommt. Daraus resultiert die Gegenwart als konstanter Streit. Diese Form der Auseinandersetzung macht die Gegenwartskunst aus, deren Kriterien deswegen nicht extern begründet werden können: An der Vermittlung von Geschichte, Kritik und Kunst zeigt sich damit deren konstitutive Autonomie. Werner Busch zeigt in Vergangenheit wird nie wieder Gegenwart. Zum Fremdwerden zitierter Kunst den Anfang eines solchen kritischen Vergangenheitsbezugs der Kunst in der anbrechenden Moderne. Indem die idealistische Vorstellung göttlicher Einheit „von einem Eindringen der Zeitvorstellung abgelöst“ wurde, stellte sich die Frage nach dem selbstdefinierenden Geschichtsverhältnis. Joshua Reynolds theoretische Stellungnahme zum Zitieren von Kunst steht paradigmatisch für diesen Umbruch. Reynolds argumentiert für ein synkretistisches Zitierverfahren, da künstlerische Erfindung immer auf Kunst basiere: „Nothing can come from nothing.“ In der Fortsetzung der Tradition liege überdies die Legitimationsbedingung von Autorschaft.

Anhand konkreter Arbeiten wird schließlich die jeweils gegenseitig konstitutive Verschränkung von Kunstgeschichte und Gegenwartskunst in konzeptuellen Werken der Nachkriegszeit weiter verhandelt. Sabeth Buchmann untersucht in Geschichte auf Probe kunsthistorische Narrative in konzeptuellen Arbeiten seit den 1970er Jahren. Im Gegensatz zum angestrebten Bruch mit einer „Naturgeschichte der Moderne“ in den 1960ern, der sich in einer Gegenwartsbehauptung eines Hier und Jetzt sammelte, als auch den Zukunftsexperimenten der Avantgarden ist in den 1980er und 1990er Jahren eine künstlerische Praxis entstanden, die sich Verfahren des Erinnerns, des Gedächtnisses und des Archivs widmet. Darin zeigt sich eine Heterogenität des Verhältnisses von Kunst und Geschichte, welche den Begriff des Zeitgenössischen selbst anachronistisch macht. Anhand von Arbeiten von On Kawara, Félix González-Torres, Tom Burr und Danh Vo zeigt Buchmann wie konzeptuelle Arbeiten Objektsequenzen mittels einer Engführung von „Lebens- als Zeitform“ rekapitulieren. In solchen mit biografischer Zeit aufgeladenen historischen Sequenzen oder Tableaus werden identitätskonstitutive, biopolitisch wirksame (kunst-)geschichtliche Narrative, Modelle der Autorschaft und der künstlerischen Identität denaturalisiert. Kerstin Stakemeiers Beitrag Medienportraits. Äquivalenz, Subjektivierung und Postmoderne beschäftigt sich mit der Verschiebung der Konzeption von Freiheit der (und von) Kunst im Umschlag von Spätmoderne zu Postmoderne, ein Streit, den die kunsthistorische Kanonisierung systematisch übergangen habe. Die radikale Kommodifizierung der Kunst in den 1980er Jahren hatte die modernistische Freiheitsbehauptung in Frage gestellt, sodass KünstlerInnen neue Wege zur Subjektivierung der künstlerischen Form suchten. Strategien, künstlerische Medien „gegen ihre Warenförmigkeit spezifisch zu machen“, wurden entwickelt, etwa bei Kathy Acker „Cut-Ups und Cut-Ins (in) der (die) vorgefundene(n) Kultur“. Enteignung und Aneignung zugunsten einer Resubjektivierung bilden den Gegenentwurf zur anhaltenden Vorstellung „genuiner künstlerischer Imagination“ im „spätmodernistischen Rückzugsgefecht“. In Christa Blümlingers Beitrag Film als Kunst der Passagen. Apichatpong Weerasethakuls Variationen über „Boonmee“ bildet das Problem einer Geschichte des Films den Ausgangspunkt. Durch die „Variabilität des Objekts Film“ kann nicht von einer Filmgeschichte gesprochen werden. Gerade darin erkennt Rancière ein revolutionäres Potenzial, indem das Medium in dieser Ungreifbarkeit seiner Forderung nach Fiktion, dem Dissens zugunsten einer Neuordnung des Sinnlichen, entspricht. Eine „Hybridität des ‚Lebens der Formen‘“ sieht Blümlinger in Weerasethakuls Arbeiten angelegt, in welchen in einer transgressiven Medialität „Arbeit am Dissens“ betrieben wird. Anhand des Bezuges von Paulina Olowska auf die weitgehend unbekannte polnische Künstlerin Zofia Stryjeńska verhandelt Vera Lauf mit Tradition der Innovation. Genealogien der Moderne bei Paulina Olowska das Verhältnis zeitgenössischer Kunst und Kunstgeschichte an einem ausgewählten Beispiel. Olowska führt in den Akt der Aneignung distanzierende Perspektiven ein. Die erzeugte Subjektivierung, einer künstlerischen ‚Heimat‘ und einer Traditionslinie, die in der Inszenierung ihres Vorbildes liegt, wird gebrochen und lässt in einer Art Horizontverschmelzung Kunstgeschichte und Gegenwartskunst einander affizieren. Die „komparative Perspektive“ von „Präsentationsmustern, Ästhetiken und Techniken“ resultiert in einer „Neubewertung der Logiken“ von Kunstmachen und künstlerischer Kreativität. Beatrice von Bismarcks Beitrag schließlich beschäftigt sich mit der Geschichtlichkeit von Ausstellungen. Der Teufel trägt Geschichtlichkeit oder im Look der Provokation: When Attitudes Become Form – Bern 1969/Venice 2013 widmet sich der epochemachenden Ausstellung Harald Szeemanns und ihrem „Reenactment“ der Fondazione Prada 2013. Der Anspruch auf eine möglichst „originalgetreue Rekonstruktion“ lässt in dieser Unmittelbarkeit – dem Mangel kritischer Reflexion – die Ausstellung selbst zum materiellen Index der gegenwärtigen Kunstwelt gerinnen. Im resultierenden Kontrast zur ursprünglichen „Show“ zeigt sich die historische Transformation der Kunstszene an, die „Kapitalisierung von Subjektivität“, in der etwa KünstlerInnen „zu Rollenmodellen der postfordistischen Arbeitswelt“ geworden sind. So verdreht sich die von Szeemann speziell gegen Handelstauglichkeit eingesetzte konzeptuelle Ausrichtung der ursprünglichen Ausstellung nun zu einem Ort, an dem die Beteiligten „ihren ökonomischen und symbolischen Wertzuwachs zur Aufführung bringen“, in dem es nur mehr um ein von Prada gesponsertes „Geschäft mit der Sichtbarkeit“ geht.

Die Frage nach dem Zusammenhang von Kunstgeschichte und Gegenwartskunst scheint auf mehreren Ebenen interessant und aktuell. Beispielsweise liegt es nahe, dass eine Gegenwartskunst, die sich explizit mit dem Thema der Geschichte beschäftigt, auch ihre eigene Geschichtlichkeit reflektiert. Wenn sich diese nun als historische und ideologische Konstruktion zeigt, wie kann dann die Bezugnahme auf einzelne Positionen legitimiert werden? An die Stelle einer kompletten Zurückweisung von (historischem) Kontext, die aus dieser Feststellung auch folgen könnte, stellt der Band verschiedene Strategien des kunstgeschichtlichen Bezugs vor, worin gerade mittels anachronischer Verknotungen Aktualität erzeugt wird. Andererseits sind im Kontext einer Gegenwart, die die Form eines homogenisierten Spektakels annimmt, spezifische Strategien zur Konstruktion von Abständen notwendig. Und zwar nicht nur, um überhaupt erst historische Differenz zu erzeugen, sondern auch, um das anachronische Potenzial des Vergangenen zur Erzeugung von Heterogenität der Gegenwart dienstbar zu machen. Die Frage nach Modellen der Autorschaft, die speziell im Zwiespalt von modernistischen und postmodernistischen Werkformen Kontur gewinnt, bietet dabei ihrerseits einen produktiven Anstoß zur Auseinandersetzung mit postfordistischen Subjektivitätskonstellationen der Gegenwart und den Problemen zeitgenössischer Kunstproduktion.

Die Expertise der versammelten AutorInnen konzentriert sich spürbar auf die Nachmoderne: Die Moderne, die beinahe als universaler Referent für „Kunstgeschichtlichkeit“ einsteht, wird nirgends konkret, sondern nur mittels allgemeiner Begriffe aufgerufen: Grundsätzlich wird die modernistische, konstruktive Utopie gegen die poststrukturalistische Dekonstruktion ausgespielt. Dabei wird die Perspektive einer phänomenologisch orientierten Kunstgeschichte auf diejenige von Michael Fried in Art and Objecthood reduziert und in der Folge ausgeklammert. Obwohl – wie auch Frieds Arbeit zum 19. Jahrhundert zeigt – ein solcher Erfahrungsbegriff eine interessante Ergänzung darstellen wie auch eine stärkere Erdung im materiellen Bestand hätte bewirken können. Dabei bestünde das Ästhetische gerade auch in einer Form des Nicht-Diskursiven, wie es Rancières Kategorie des Dissenses vorführt: Die nicht einfach unter Begriffe subsumierbare Erfahrung von (anachronischer) Alterität hat einen wesentlichen Rückhalt im Ästhetischen. Der Schwerpunkt auf post-konzeptuelle Positionen scheint eine solche Herangehensweise zumindest zu erschweren, setzen solche doch zumeist auf die Diskursivierung von Ereignissen und Erfahrungen.

Eine Tendenz zum Idealistischen, die schon in Rancières Aufstellung des Anachronischen liegt, wird von den meisten AutorInnen übernommen: Der revolutionäre Umschlag soll von gedanklicher Arbeit – sprich in „Gedanken-Sprüngen“, wie anknüpfend an Rancière formuliert werden könnte – motiviert sein. Eine materialistische Analyse der Kanonbildung fehlt ganz; die im Band besprochenen künstlerischen Positionen sind fast ausschließlich dem oberen Segment eines globalen Kunstmarkts entnommen. Die anachronischen Rekonfigurationen zugunsten einer heterogenen Kunstgeschichte mit all ihren Konsequenzen etwa für Subjektivitäts- und Autorschaftsstrukturen laufen so Gefahr im Status bloß überbaulicher Synthesen zu verbleiben, während die unterirdischen Kontrollmechanismen schlicht beim Markt liegen. Darin scheint sich, neben der vorauseilenden Diskursgeschichte, auch eine präreflexive Synchronisierung durch das Kapital anzuzeigen. Auf der anderen Seite scheint Rancières Konzeption des Anachronischen und der „Aufteilung des Sinnlichen“ schon per definitionem im Konflikt mit einer etablierten internationalen Kunst, wie sie heute institutionell aufgestellt ist, situiert. Es ließe sich so in letzter Konsequenz diskutieren, ob in Zeiten der Dezentralisierung und Multipolarisierung – während sich herausstellt, dass die transnationalen Utopien als Maskeraden für hegemoniale marktwirtschaftliche Strategien missbraucht werden und wurden – im Wunsch nach einer „globalen Kunst“ (wie etwa Joselits Vorschlag eines „internationalen Stils“ suggeriert) nicht selbst ein regressiver Anachronismus steckt, der dem politischen und technologischen Stand des ausgehenden 20. Jahrhunderts verpflichtet bleibt und nur in die Allianz mit dem globalen Kapital führen kann. Ein aus der anachronischen Koppelung von Modernismus und Postmodernismus zu ziehendes Fazit der Lektüre der Publikation könnte deswegen die Einsicht sein, dass der kritische Diskurs konkret lokalisierte, konstruktivistische Produktionsarme bräuchte, die Alterität herstellen (und keine postzeitgenössischen Spekulationen), so wie die Wirtschaftspolitik – und das wäre eine wirtschaftshistorische Anachronie – einen new „New Deal“ (und keine spekulativen Strategien der Zentralbanken) braucht.

[1] Vgl. etwa: Yilmaz Dziewior (Hg.), Wessen Geschichte. Vergangenheit in der Kunst der Gegenwart, Texte zur Kunst, Nr. 76, Köln 2009.

Posted in Ausgabe 11, Buchrezensionen

Tagged Gegenwartskunst, historizität

Comments Off on Heterogenität einer global(isiert)en Kunst?

A Breath of Fresh Air

Johanna Braun met Laure Murat in Los Angeles to have an extensive talk about the art and politics of madness, its historical as well as cultural significance. Murat, a cultural historian who specializes in the history of literature, psychiatry, and gender studies, also has a background as an art critic and is passionately transgressing disciplines, while showing unconventional and furthermore inspiring approaches to what it means to be a contemporary academic.

Johanna Braun: We meet right in the middle of the heated debates of the US presidential elections. The theme of madness seems to overshadow the media coverage of the political events. Your book The Man Who Thought He Was Napoleon. Towards a Political History of Madness (2011/2014)[1] – which won the prestigious Prix Femina Essai nonfiction prize –showed in depth that this phenomenon is nothing new but that politics and mental illness are more intertwined than one would think. While your book focused on the 18th to late 19th centuries in France I think your findings are also very relevant for a US American setting. How would you describe the similarities and differences of handling the mentally-ill in praxis and “insanity” as a point of reference during political debates?

Laure Murat: Last summer, the American Psychiatric Association issued a warning about “wild diagnoses” concerning Donald Trump, whom some doctors publicly considered a serious “sociopath”. Jeffrey Flier, former Harvard Medical School Dean even tweeted: “Narcissistic personality disorder. Trump doesn’t just have it, he defines it.” Although it may be true, it is problematic and unethical to make this kind of statement without any examination and without being granted authorization. More importantly, I think it is counter-productive: the more you resort to madness, the less you are analyzing the political and intellectual dangers at stake. “Madness” is often a way to get rid of a bigger problem. Better decipher the danger than jump to a conclusion and claim for a “disorder”. It works for terrorism as well. We have to be very careful with words when it comes to madness. “Sociopath,” “crazy,” “insane,” are mostly used in a familiar sense that doesn’t necessarily reflect a true condition. Trump is certainly dangerous. And he definitely has “crazy hair.” Ted Cruz had a “normal” haircut but was at least as “insane” and dangerous as Trump – a problem very few commentators pointed out. Public opinion, blogs, op-eds, statements in journals or newspapers during elections are interesting for that reason among others: it shows how the concept of “madness” is, first and foremost, ideological and based on prejudice. It is usually a judgmental category that leads to confusion. What worries me the most, now, is that the actual political situation is barely “under control.” Trump unleashed a kind of violence and hatred in public discourse that, I am afraid, is going to last and to severely disrupt the social climate.

Johanna Braun: What I find also very interesting during the current presidential elections is the discussion of the „Insider“ versus the „Outsider,“ (the German word “Quereinsteiger_in” would be a better description) and the strong belief that the “Outsider” is the one who can change a corrupted system. Without wanting to compare apples with oranges: I love the story of how you found your passion for teaching while you were a Visiting professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts of Paris, (1997–1998) which led to your decision to undertake yourself an academic training. Your unconventional career path that led you from a comfortable life as a successful art critic in Paris to a new beginning in Los Angeles is inspiring. Could you tell us how it came to this life changing decision?

Laure Murat: It was a long process. I have always been a very mediocre pupil at school. My obsession was to leave home and to enter into working life. At 19, I was lucky enough to get an internship in an art journal that finally hired me. That is how it started. Ten years later, I was invited at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris to teach the “theory of art criticism.” Here is the weird thing: I hated school but I discovered I loved teaching. Once on the other side of the desk, it was a completely different story. I could explain, share, discuss freely. It was such a great experience. I realized that most of the teaching is a failure because it lacks desire. I discovered that I had this desire, related to what the Ancients call libido sciendi. No matter what teaching or learning means, the issue is about excitement regarding knowledge. Unfortunately, I couldn’t stay at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Not only was it a “visiting professorship” for 6 months non-renewable, but I didn’t have any credentials to apply for a “real” job – no diplomas of any kind. I didn’t have the courage to go back to the university (or rather to “go” to the university, given I’ve never been to). A few years went by. I published two books in the meantime, which got some public and critical recognition. At that time, a friend of mine told me that people with my unusual profile could enroll in a specific program at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales that gives way to a PhD program. I wrote the equivalent of a master thesis and got into the PhD program. But when I was about to enter the PhD program and enroll in my first classes ever, I was invited to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Of course, I accepted the invitation and wrote my dissertation there. The same year, I was invited to apply to UCLA. And I got the job. I went back to Paris, defended my dissertation, got my visa, and flew to Los Angeles.

The result was that, in January 2007, I was in front of a class of young American students while I haven’t been taught myself ever, although I got a PhD. I had to invent something. I thought: what would keep me awake? To make an audience alert is a very complex task. It is a performance. But it is not so difficult. You only have to make clear the following: what is the question? What happens when someone is reading a text? One likes it or not, can summarize the plot, can talk about psychology of the characters. But no one, usually, is able to tell: what is the problem at stake? The use of the Internet has worsened this issue. The web provides answers, a flow of answers. But it doesn’t trigger questions. That is my role. Ask the students: what is the question? What is your question?

Being an “outsider” or a “newcomer” helps. I was not trained. I was not in the system. I will never be, in a way. There is a very popular program on American radio called “Fresh air.” I would like, ideally, to be the “fresh air.” Academia, although less in America than in Europe, sounds too often in automatic pilot. The outsider is not necessarily the good one. She or he allows another point of view. To go back to your comparison: Trump is not an “outsider.” He is the mainstream businessman who threatens Washington. Corruption against corruption. Private against public. I don’t view myself in this kind of battle. What I would like is to bridge the gap between disciplines and, mostly, between the University and a larger audience. I would like to make the academic language “audible.”

Johanna Braun: This is a great analogy, because the way you write does very much feel “fresh” and “refreshing.” Your writing is very inviting and narrative and therefore expands the often narrow readership of the academic community. The widespread media attention, as well as the critical praise, you receive for your work speak for themselves. How would you describe your position within academic discourse on one hand and your position as a public intellectual on the other? Do you follow specific principles or school of thoughts?

Laure Murat: For a French citizen, the distinction between an “academic” or “university professor” and a “public intellectual” is not completely relevant. Whatever his/her job is, the French will always be the one who will ask: “That works well in practice, but how does it work in theory?” Every week, literature, philosophy, social sciences are on the headlines of the newspapers. It is part of everyday life and conversation. We have a whole radio station dedicated to intellectual issues, called France-Culture.

This way of thinking is also contaminating other media. A good example is that we don’t have any real distinction between “university presses” and “trade presses.” like in the US. The major presses (Gallimard, Le Seuil, Fayard, Flammarion, etc.) are welcoming professors and public intellectuals who have something to say, in an audible way. That’s it. There are also specific publishing houses, devoted to purely academic and more specialized work, but it is quite marginal.

I never feel I belong to an “academic community” that would be separated from public debate. For instance, every month, I give an op-ed to the daily newspaper Libération, where I write about anything that crosses my mind: the destruction of Palmyra, contemporary feminism, but also the fashion of “talkative t-shirts.”

Johanna Braun: Although, you are so open to any relevant topic of the moment and its cultural impact, your long-lasting interest in art history and the artist as a figure of cultural significance prevails. The themes of madness and its close relationship to the arts are persistent throughout your work. Already in the biography La Maison du docteur Blanche (2001) – which won France’s prestigious Goncourt Prize for Biography and the French Academy’s Critique’s Prize – you followed the father and son Esprit and Emile Blanche who treated famous 19th century artists who „lost their minds.“ Your current research Project Women as Symptoms, or Madness at Work – for which you received a Guggenheim fellowship – also focuses on the triangle of the artist, the artistic work and the contagious madness that the work produces. Why do you think the artist has this special affiliation to the mentally-ill – or should I rather say gets painted as having this connection – and why is the artist a recurring figure in the development of the mental institution?

Laure Murat: It is a very complicated issue that it is not possible to address in a few lines. But let me say a few things. First, madness doesn’t make you an artist (otherwise, all asylums would be overcrowded with Van Goghs), exactly as LSD doesn’t make you a poet. Second, if some artists proved to be insane, it shows that “mentally-ills” can be artists as well as artists can be mentally-ill. It goes both ways. It is always dangerous to “romanticize” madness. Finally, one can say that there is a comparable “structure” between aesthetic creation and the effort of “re-construction” of the psychotic patient. It has to do with an archaic mode of representation – before the famous “mirror stage” and the constitution of the ego. The goals are not the same: the artist is looking for aesthetic pleasure; the psychotic patient for a kind of reparation.

Johanna Braun: In your brand new book Ceci n’est pas une ville (Flammarion, 2016), the table seems to have turned: you are haunted by the question if one can fall passionately in love with a city. In your case the love interest is the city of Los Angeles. With the ongoing academic and public interest in Objectophilia, it is striking that with examples as Eija-Riitta Berliner-Mauer, Erika Eiffel and Amanda Liberty, it seems that there is an intense and almost uncanny connection between women and urban places. Here, a different kind of “madness” comes into play: It is interesting how especially women go “crazy” over their love of public spaces. Could you tell us more about your new book and would you go as far as to describe yourself as being madly in love with L.A.?

Laure Murat: After ten years living in Los Angeles, I realized that I had a special relationship to the city. But I don’t think I fetishize it, as it is the case in objectophilia. On the contrary. For me, L.A. is more like an imaginary, versatile, flexible space. Women usually have issues talking about their experience in public urban places, as if they had internalized their social assignment to the private sphere. I tried to address this issue, in analyzing the erotic tension one can feel in a city and why. One of the answers I found is that Los Angeles provides me a sense of freedom. In L.A., a horizontal and never ending city, without center nor monuments, you always have a perspective, both in the literal and figurative sense. Your body never feels “confined” or blocked in any way. The horizon is always open as is the future.

Laure Murat (*1967), is professor in the Department of French and Francophone Studies, the Director of the Center for European and Russian Studies and in addition also serves as faculty advisor for the LGBT Studies program at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is the author of the critically well received book The Man Who Thought He Was Napoleon. Towards a Political History of Madness (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014)* and her last book is entitled: Ceci n’est pas une ville (Flammarion, 2016).

Posted in Ausgabe 11, Interviews

Tagged gender studies, laure murat, psychiatry

Comments Off on A Breath of Fresh Air

On Benjamin Patterson

Benjamin Patterson, who saw over fifty years of experimental art production as a Fluxus co-founder and artist, passed away this summer. Born in Pittsburgh May 29, 1934, Patterson was an African-American bassist with limited professional opportunities in segregation-era United States. Instead, Patterson circumvented existing racial barriers by relocating to Canada and performing with symphony orchestras, at which point he took closer interest in electronic music.[1] A trip to Germany redirected the course of his career to experimental art production after a negative encounter with acclaimed Karlheinz Stockhausen. The fallout was brief. Shortly thereafter, he attended and even performed in Cologne alongside major persons such as American experimental musician John Cage. Patterson later held a central role to the formation and continuation of Fluxus, a group associated with anti-art, neo-dada and proto-conceptualist ideas in performance.[2]

A principal Fluxus artist, Patterson supplied details about the group’s history and choices of media in numerous interviews over the years. For example, his conversation in the US Army magazine Stars and Stripes introduced Fluxus to general audiences in Wiesbaden. Emmett Williams, a fellow Fluxus artist and the magazine’s editor, also partook in the “tongue-in-cheek” conversation on their antics.[3] More recently, Patterson contributed significantly as the creative director of Fluxus’ fiftieth celebration in Wiesbaden, its adoptive birthplace.[4] Obituaries following Patterson’s passing remark upon his prominent role, his many firsts, and also poetically treat his overlooked contributions to histories of experimental art.[5] In this article, I contribute to reflections on Patterson’s significance by concentrating on one of many interviews from his lifetime.

Indeed, I argue that his self-authored interview “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” from 1991 became a linchpin from which Patterson developed a public platform and tangible presence within Fluxus history.[6] I focus on the life of the essay and connect it to Patterson’s engagement with writing as central to his art practice. Exploring moments behind this publication provides an alternative way to respond to discussions related to Benjamin Patterson’s art career — particularly, his absence within Fluxus narratives.

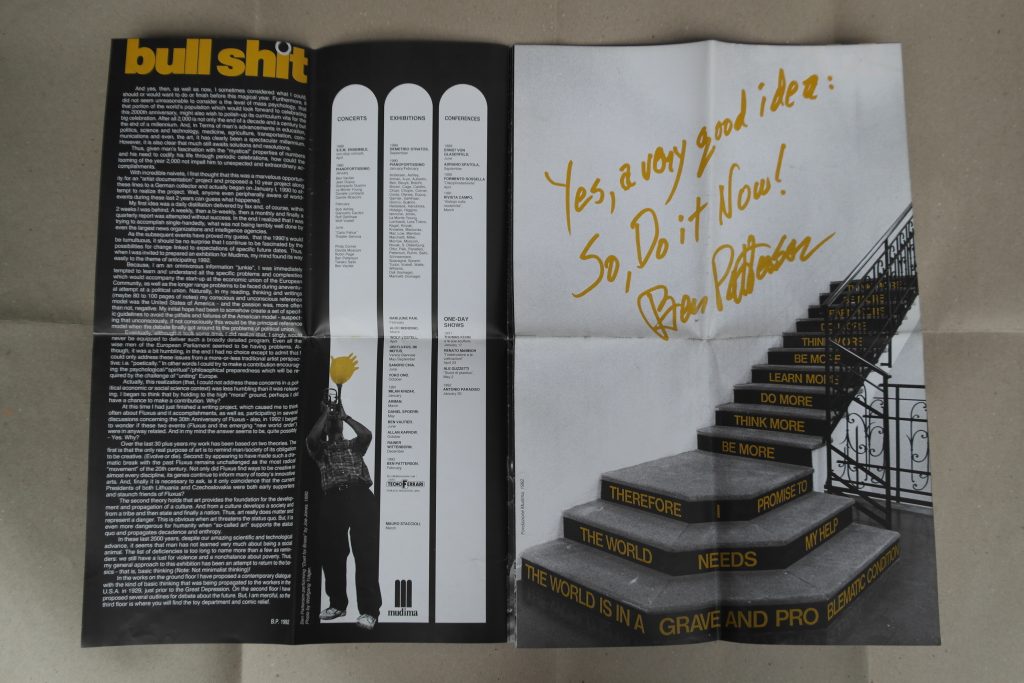

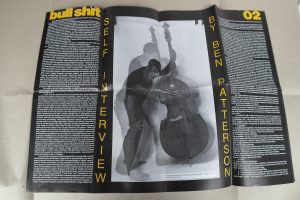

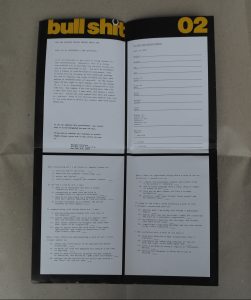

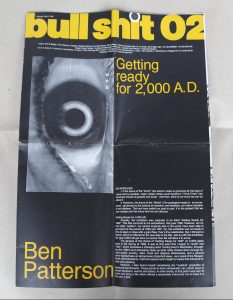

I begin with the second appearance of “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” as “Self Interview.” This text reappeared for Patterson’s first solo show in 1992 at Fondazione Mudima in Milan, which published the exhibition-specific periodical Bull Shit. Patterson’s special issue of Bull Shit, titled Bull Shit No. 2, featured two texts by him, several images, and artwork as supplemental material for his show Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. This issue is the only time that any of Patterson’s other writing accompanied the interview, meaning that he was the sole author of the issue. The multiple appearances of this interview extended its life, accessibility, and thus contexts behind Patterson’s relationship to art making. In this essay, I link all five lives of his interview to consider writing as central within his art practice.

Of note, “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” first debuted as a standalone article in Kunstforum International in 1991, propelling his profile to a German-speaking public. Patterson republished it in English and under the heading “Self Interview” (1992) in Bull Shit. Its third and fourth appearances in 2011 and 2012, in From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany and Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us respectively, existed alongside a wave of scholarly interest in highlighting his role as a leading Black experimental artist. Its fifth, and now final, form appeared in 2013 as “Fortsetzung,” in which Patterson updated audiences about his rise in popularity, a rise leading him to assert he, “no longer enjoy[ed] anonymity.”[7]

Fig. 1: Benjamin Patterson, Bull Shit No. 2, cover page, featuring “Background” by Benjamin Patterson, February/March, 1992.

In 1992, Patterson reused the entire unaltered text from his 1991 self-authored interview. It functioned as the main essay for his issue of Bull Shit, and for his multileveled solo exhibition at Fondazione Mudima. The interview progressed through a series of planted questions, detailing Patterson’s career overview as well as positing judgments about Fluxus as a collective. His choice to republish the interview indicates a desire to familiarize different audiences with his knowledge of Fluxus history. It similarly provides an additional layer for approaching how Patterson conceptualizes ideas. His special issue Bull Shit. No 2 includes a separate text titled “Background,” which precedes “Self Interview” and articulates themes integral to his exhibition Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. In an attempt to lay bare his exhibition framework, Patterson’s texts performed like scaffolding, providing entryways for audiences to understand practices and theories for an exhibition prompted by the end of a decade and a century.

The circumstances behind the interview’s second life, however, in Bull Shit remained unannounced in the issue. Neither Gino di Maggio, an enthusiastic Fluxus collector and founder of Fondazione Mudima, nor Patterson, elaborated explicitly on such intricate points as editors. They listed it simply as “Self Interview,” and the eponymous in-line reference weakly clues new audiences to its original title. The text’s introduction also offers little support for a deeper understanding of its preexistence. I am choosing to magnify its presence, reading it visually and textually as part of Patterson’s practice in writing and viewer engagement. Writing and imaging were critical modes of communication that undergirded much of his early works on paper, his puzzle poems and his operas. It is therefore productive to treat this interview as a comparable moment within his creative process.

Fig. 2: Benjamin Patterson, “Seminar II”, Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performance and Other Projects 1958-1998. Black binder, white facsimiles. 32 x 29 x 5 cm.

Two quintessential examples from his oeuvre are the anthology Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performances and Other Projects 1958-1998 (1999) and Methods and Processes (1962). Prose is a distinctive characteristic in his Black and White File. Readers encounter heavy amounts of text as guidelines to performances or as texts for events. Comparatively, his first artist book Methods and Processes marked a “sort of the return to visual work, as it were,” evident from his pairing of texts and images for interpretative exercises.[8] Patterson’s comprehensive assembly of materials reveals that he approached publishing as a way to ensure accessibility.[9]

Whereas Patterson did foreground some explanatory details at the introduction of “Ich bin froh” (and its subsequent titles), I am particularly interested in what he visualized or obscured. Accessibility may offer resources from which to build upon, but it cannot always clarify context. At the outset, Patterson wrote “Dieter Daniels suggested that he would like to do a piece on Benjamin Patterson in a special Fluxus issue of Kunst Forum,”[10] Patterson’s dislike for interviews led to Daniels suggesting that he “do the whole interview of myself by myself.”[11] Outlined in this playful, albeit serious, first and third-person work, are ideas and accounts; left unstated are the editorial and visual decisions impacting the issue.

Patterson communicated working theories about his practice in his special issue of Bull Shit, and established the tenor of the exhibition through visual forms. His “Background” text, a separate and preceding text as I mentioned above, supports my first point. In gray, he wrote: “Actually, this exhibition was originally to be titled ‘Getting Ready for 1992.’ This title occurred to me somewhere, mid-year 1990. However, as it is now clear, neither I, nor almost anybody else in the world, have been able to get ready for the events of 1990 and 1991.”[12] “Background” laid a foundation for a show framed by the ensuing years, beginning with the 1990s and concluding at the millennial turn. If the single, disembodied eye on the issue’s cover was not distressing enough, Patterson’s words suggested the need to brace oneself.

Rather than frighten readers, Patterson sternly suggested that the present and future moments were ripe for productive conversation about social conditions. Shifting back further than 1992, he cited 1989 as the real point of departure for Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. at Fondazione Mudima. “It was at that point that I began to ’smell’ that ’odor’, [sic] which precedes a changing wind,” he noted about living in New York City at a time of escalating social problems.[13] Patterson found himself surrounded by class and racial divides that worsened under President Ronald Reagan’s “Reaganomics.” Reagan’s neoliberal economic policies of lower taxation and de-regulation were critiqued widely as placing business before people. Just as well, 1989 signified more than US trends. It evoked a sense of relief and hope attached to the demolition of the Berlin Wall, which stood as a remnant of divisiveness from World War II. Its “fall” subsequently foreshadowed Germany’s reunification, which crystallized a sense of progressive change in the western global imaginary.

The impression of progress ran parallel in Patterson’s special issue as readers advanced the folios. The spread contained forms with literal, and in my opinion, metaphoric meaning. Once individuals turned from the cover page to the next, they encountered a photo of Patterson trumpeting to an undetectable horizon. As he plays a trumpet covered by a plastic glove, he stands beneath three sections of forthcoming events at Fondazione Mudima that resemble white columns: “Concerts,” “Exhibitions,” and “Conferences/One Day Shows.” Each column forms a white silhouette of a classical arch, repeating Mudima’s iconic black logo at the bottom, which also situates Patterson’s clipped image within a symbolic context of tradition, invention, and grandeur.

To the right-hand side, an installation photo of a staircase with vinyl letters covers the entire page. The image indicates that visitors would travel up a staircase of declarations to view other exhibition works. This one in particular had a bulky bullnose that narrowed after three steps. The ordinary movement up a staircase becomes an ascendance across elongated assertions and declarative vinyl on every riser. It recalls text from “Background,” such as Patterson’s comment that beginning of new years leads to a type of introversion for “considering the ‘mystical’ properties of temporal benchmarks.”[14] Like New Year’s resolutions, one moves from premise to affirmation.

The first step states, “THE WORLD IS IN A GRAVE AND PRO-BLEMATIC CONDITION.” The next step, “THE WORLD NEEDS MY HELP,” signals a move towards solutions. Patterson wrote out in vinyl for each subsequent step: “THEREFORE I PROMISE TO/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE/ DO MORE/ LEARN MORE/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE/ DO MORE/ LEARN MORE/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE.”[15]

Viewed together, the verso and recto pages imply upward movement and resonate with Patterson’s conclusion at the end of “Background.” Among other topics in the text, readers would also learn that Patterson had initiated a ten-year artist documentation project to capture the onslaught of worldwide events. The initiation of the Gulf War by the US (1990); German Reunification (1990); and the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in apartheid South Africa (1990) were historical shifts that took Patterson’s attention. Related to the development of the European Union, his featured works in the show were contributions for “encouraging the psychological/‘spiritual’/philosophical preparedness which will be required by the challenge of ‘uniting’ Europe.”[16]

A supplement to the exhibition, his special issue “Bull Shit No. 2” similarly performed ideas of preparedness and reflection. Each text within, “Background” and “Self Interview,” elaborates on Patterson’s theories of art and Fluxus history. He flatly laid out parameters of both, sharing that he completed a “writing project” prompted by Fluxus’ upcoming thirtieth anniversary in 1992.[17]His first theory was that art existed out of the humanity’s need to be creative, or as he stated “evolve or die.”[18] Second, art created a basis from which culture extended by “development and propagation.” Taking the position that positive social change moved slower than societal development, Patterson envisioned this exhibition as his “return to the basics,” or using art for necessary progress.[19] This “return,” I believe, also references actual changes in his own life.

Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. occurred two years of sustained momentum with his career. After relocating to Germany, Patterson already had two recent solo shows, completely severing his so-called “retirement from the unstable life of an experimental artist in New York” since the mid-1960s.[20] Patterson described the years between 1965 and 1988 as the period where he pursued a normal life, shorthand for parenthood and a regimented lifestyle. The life of a Fluxus artist offered little financial ability, and so he took up library, director and freelance positions over the years.[21] All the while, he showcased or performed a range of works at varying institutions.[22] His solo show “Ordinary Life” (1988) at Emily Harvey Gallery signaled his “return” to working as an artist, jumpstarting a tremendously prolific period to come. As the gears turned, his interview created unobstructed space for Patterson to enunciate his experiences and articulate a history of Fluxus.

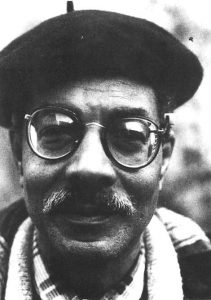

The interview became an opportunity to fashion a public identity and develop an archival footprint in public. For example, Kunstforum International’s “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” includes a stunning monochrome portrait taken by Wolfgang Träger, an acclaimed documentary photographer. Patterson smiles pleasantly at the camera while donning a wool beret, and a plaid shirt and sweater combo beneath a coat — sartorial cues of an urbane artist. After Träger’s close-up follows reproductions of Patterson’s artwork or material supporting exhibitions, from an exhibition card to performance documentation. The last images are of assemblages and installations, and the visibility of this material not only serves as evidence of works but also an unrestricted art practice.[23]

Patterson’s flexible approach to material and objects is noticeable in the interview’s format change in Bull Shit, and suggests he considered the context of its second republication. Not only did he extend its afterlife, but he also added another layer in presentation. With an entirely different set of images to accentuate his narrative, the interview appeared in English and served as connective tissue between himself and English-speaking audiences. Patterson’s customized issue “Bull Shit No. 2” doubly reflected the artist-led direction of the periodical Bull Shit at the foundation.[24]

Bull Shit positioned the voice of the artist front and center. In this way, it recalls western conceptualist strategies of curating during the late 1960s. Lucy Lippard’s and Seth Siegelaub’s portable catalogues, created from artist-submitted material, are just two major examples. Fluxus artist Dick Higgins’ Something Else Press was also integral to circulating artist writing and work. In the context of the move to reach audiences beyond the “white cube,” Patterson’s special issue was a setting to expand networks and information sharing.

Readers of any interview version would learn about Patterson’s origin story; a narrative beginning with his ambitious attempts to integrate US symphony orchestras, and his subsequent involvement as a Fluxus artist. Patterson’s planted questions were followed by descriptions of a lifetime of achievements that bordered on the epic and personal history, essentially creating a roadmap of his experiences. Detailed encounters manifest through memory, such as Patterson’s responses to living in New York or his subtle references to racial experiences that spur questions about Fluxus’ internal harmony: “to varying degrees they all became friends of a sort. But now I recognize that we simply did not share the deep-rooted (albeit hidden) alienation that I lived with as the only black in this crowd.”[25]

His use of the term “hidden” implies a scarcity of moments in which he comfortably spoke with his peers about race. Race was one of many constructed categories informing Patterson’s positionality. He was Black, middle class, college-educated, travelled and so forth. Personally, Patterson acknowledged race as relevant, which he also linked to his use of humor.[26] The slippery balance between indirect referencing and verbalization, revealing and concealing, presence and absence, also plays out in the rest of “Bull Shit No. 2.”

Unlike the clear portrait by Träger in Kunstforum International, Italian photographer Fabrizio Garghetti’s photograph of Patterson in Bull Shit seems hollow and illegible. In this moment, Patterson re-performed Variations for Double Bass during 1990 in Verona. The photograph echoes Patterson’s active presence in art-making by shifting the focus away from his artistic identity to his bodily movement. Printed evenly between each page, the image also inflects the context of the surrounding text. The three semi-transparent Pattersons, standing, playing and reaching out, link with his listing of artistic influences in the interview. The placement of such an image supplies more contexts for it and its neighboring text.

Similar moments occur throughout the following pages, such as a photo of Patterson leading blindfolded audiences along the streets matching his critique that Fluxus artists never reached out to him about civil rights marches. If art is generative and serves the needs of social development, Patterson suggested that Fluxus failed in this regard. He stated, “All [Fluxus] really did with its reputation for radical aesthetics was to provide a safe refuge and masks for a bunch of well meaning artists.”[27] As a platform in which he could concretize his presence and voice in Fluxus to a wider public, “Self Interview” pre-emptively addressed the biographical and the personal.[28]

“Self Interview” is a negotiation of Patterson’s history within Fluxus’ history. It thereby familiarizes readers with a certain level of visibility prior to, and after 1988. Thus, photos of his re-performances, work and installations, could engender conceptual and practical questions. Who did Patterson envision as his audience? Who was his public?[29] What was the reception of his work in the past, at that moment, and today? To whom was he visible or invisible and how does that affect contemporary engagement with his work? How fully does the historical record account for his international art practice? More scholars are considering similar sets of questions as Patterson’s profile rises.

Patterson’s interview reappeared nearly a decade later once intellectuals committed to emphasizing his artistic importance. Submitted by Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, the 2011 anthology From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany featured the interview with a preface to clarify her inspiration. To Oliver, Patterson was possibly “the ‘godfather of black performance traditions’.”[30] Oliver utilized the interview as a way to amplify Patterson’s voice, this time in book format and with two photos of his performances.[31]

“I’m Glad You Asked That Question” prepared new audiences for Oliver’s

exhibition, Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us, that opened November 6, 2010, at the CAMH. His first US retrospective, the exhibition and catalogue established a US scholarly context around his history as a Fluxus artist. Accompanying the interview were topical essays addressing aspects within his work – from lenses of conceptualist theory, music and chance, to Zen. The fourth iteration of Patterson’s interview became firmly grounded within a US art historical context.

His last version, however, diverges significantly in terms of subject and presentation. A follow-up to his 1991 interview, “Fortsetzung” is Patterson’s more recent reflection on his heightened profile. In 2013, “Fortsetzung” appeared in the Nassauischer Kunstverein’s exhibition catalogue Benjamin Patterson: Living Fluxus. Operating with a similar logic as the CAMH’s catalogue, readers encountered Patterson’s externalized thoughts. He asked himself, “Now you propose to continue with more questions and answers. Why?” His answer? “Because, again, in this 50thanniversary year of Fluxus there have been many, many interviews… and again, most often, asking more or less the same questions.”[32] Patterson implied a lack of new lines of inquiry on part of intellectual curiosity in the movement and himself. Much shorter than his first interview, “Fortsetzung” concludes by asserting that Fluxus’ challenges to the parameters of art have “kept Fluxus alive and continues to inspire younger generations.”[33]

His final conclusion seems abrupt, even abridged. Yet, in a practical way, Patterson’s appeal to Fluxus’s reception forestalls need to endlessly address basic questions. Just as Patterson concluded “Bull Shit No. 2” with his piece How the Average Person Thinks About Art (1983) – using art as a central form of engaging with history – Patterson’s written conclusion of “Fortsetzung” gestures for the need to move past biography to his work.

[1] Patterson was principal bassist with the Halifax Symphony Orchestra and Ottawa Philharmonic Orchestra. He also worked as a conductor for the Philharmonic Orchestra.

[2] Benjamin Patterson, I’m Glad You Asked Me That Question, in: Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.), Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us, Houston (TX) 2012, p. 108–116.

[3] Emmett Williams, WAY,WAY, WAY OUT, in: The Stars and Stripes, August 30, 1962, p. 11. The interview was published prior to Fluxus’ festivals between September 1st to the 23rd.

[4] Histories of Fluxus accept 1962 as the year for the “official” birth of Fluxus, meaning that work and performances were then associated under the “Fluxus” term that George Maciunas first conceptualized as the title for a magazine in 1961, and then used publicly in writing June 1962 at the festival Aprés Cage: Kleinen Sommerfest Wuppertal.

[5] Andrew Russeth, Ben Patterson, Cornerstone of Fluxus and Experimental Art, Dies at 82, in: Art News, June 27, 2016, unpaginated; Hannah B. Higgins, On Not Forgetting Fluxus Artist Benjamin Patterson, in: Hyperallergic, July 6, 2016, unpaginated; Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Peeping in the Vacuum Left in that Space of ‘Darker than Blueness’ – On, Of, For, With Ben Patterson, in: Contemporary And, July 11, 2016, unpaginated.

[6] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Dieter Daniels (ed.), Kunstforum International, Fluxus: Ein Nachruf zu Lebzeiten, Nr. 115, September/Oktober 1991, p. 166–177; Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, in: Gino di Maggio and Benjamin Patterson (ed.), Bull Shit, No. 2., special issue, Milan February/March 1992, unpaginated; Benjamin Patterson, I’m Glad You Asked Me That Question, in: Maria I. Diedrich/Jürgen Heinrichs (ed.), From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany, East Lansing (Michigan) 2011, p. 335–349; Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.), 2012, p. 108–116; Benjamin Patterson, Fortsetzung: Ich bin froh, dass Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Elke Gruhn/Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden (ed.), Benjamin Patterson: Living Fluxus, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 32–35.

[7] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben: Fortsetzung*, Elke Gruhn/Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden (ed.) 2013, p. 32–33.

[8] Benjamin Patterson, in: Oral history interview with Benjamin Patterson, 2009 May 22, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[9] Patterson self-published Methods and Processes in 1962 while in Paris, and published Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performances and Other Projects 1958-1998while in residence in Wiesbaden-Erbenheim with collector Michael Berger.

[10] Benjamin Patterson, Background, in: Gino di Maggio/Benjamin Patterson (ed.), Bull Shit No. 2, special issue, Bull Shit, Milan February/March 1992, folio 1.

[11] Ibid., folio 4.

[12] Ibid., folio 1.

[13] Ibid., folio 1.

[14] Ibid., Cover page.

[15] Ibid., folio 3.

[16] Ibid., folio 2.

[17] Ibid., folio 2.

[18] Ibid., folio 2.

[19] I am exploring his idea of radicalism and radical art in my dissertation, WHO TAUGHT YOU TO THINK (LIKE THAT): Benjamin Patterson’s Conceptual Aesthetic, University of Texas at Austin, in process.

[20] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Dieter Daniels (ed.), Kunstforum International, Nr. 115, September/October 1991, p. 166–177. Benjamin Patterson had two exhibitions at the Emily Harvey Gallery in New York, Ordinary Life (1988) and What Makes People Laugh? (1989). Patterson mentions his retirement within his interview.

[21] 1967 is the year in which Patterson received a Masters in Library Science from Columbia University.

[22] For a chronology, please see Meredith Goldsmith, Chronology, in: Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.) 2013, p. 240–253. Goldsmith’s chronology of Patterson is a solid primer into his professional career.

[23] This interview includes a photograph of Educating white Folk (1988), which exemplifies humor as an important strategy with its own set of politics. In fact, he stated in his interview that “I prefer to use humor as it often provides the path of least suspicion/resistance for the implanting of subversive ideas.”

[24] Notably, Allan Kaprow had a solo show titled “7 Environments” at Mudima. His special issue included self-authored writing. Artist Takako Saito, and even Ben Vautier’s tongue-in-cheek “issue 0,“ are examples.

[25] Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, unpaginated. “They” refers to La Monte Young, Jackson Mac Low, and pop or dance artists and so forth.

[26] In his interview, Patterson stated “Please know that we blacks used satirical humor as a form of protest.”

[27] Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, unpaginated.

[28] Valerie Cassel Oliver, On Ben Patterson, 333.

[29] With regard to New York City, Patterson noted that audiences were comprised of about twenty frequenters of Fluxus activities.

[30] Valerie Cassel Oliver, On Ben Patterson, 333.

[31] The accompanying photos were Variations for Double Bass and “First Symphony Performance” accordingly.

[32] Fortsetzung, 32 (German) & 34 (English). The German version has a photo of Patterson giving a public interview in 2012. Italics are my own.

[33] Ibid., 33 (German) & 35 (English).