Johann Heinrich Füssli, Robin Goodfellow-Puck, 1787 – 1790, oil on canvas, 106 x 82 cm, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen (© Adagp Paris 2012)

Only a couple of years ago the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris (Centre Pompidou) organised a monumental exhibition on modern art and ‘the sacred’, entitled Traces du Sacré.[1] It continued where a much earlier show had left off: the 1986 exhibition The Spiritual in Art (Los Angeles and The Hague).[2] Now the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg (MAMCS) has trumped both with a grand exhibition focusing on the same topic: L’Europe des esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte, 1750-1950.[3] Obviously where Traces du Sacré and The Spiritual in Art opted for terminology such as ‘the sacred’ and ‘the spiritual’, the curators of L’Europe des esprits have made no bones about the real topic under discussion: occultism.

The MAMCS and the curators, Serge Faucherau and Joëlle Pijaudier-Cabot as well as a host of associated experts, have done a good job with this exhibition. It consists of one main show and two small complementary expositions, a film and lecture program, and a catalogue which contains a wealth of illustrations and a number of good contributions. The two small shows are in the same building but separated from the main show, to which the full first floor of the Museum is given over. Entitled L’Europe des esprits, arts et littérature, it is structured chronologically and ranges from early Romanticism to the late avant-gardes. One starts off with Les Romantiques et l’occulte and continues through Symbolismes and Abstractions et autres expressions d’avant-garde to the final part, Constellations surréalistes. The focus is exclusively European and on display are mainly paintings with some drawings and sculptures included for good measure.

The two complementary shows, though small, each highlight an important part of Europe’s occult fascination: Quand la science mesurait les esprits treats the relationship between science and occultism; and Histoire et iconographie de l’occulte: un monde d’écrits et d’images the paper trail of western esotericism generally, including occultism and spiritism.

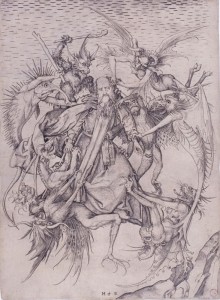

Martin Schongauer, Temptation of the Saint Antony, ca. 1473, engraving, 30,7 x 27,2 cm, Strasbourg, Cabinet des Estampes et des Dessins. (Photo: M. Bertola / Musées de Strasbourg)

Let us start with this last small exposition of primary sources: it asks much from an audience and will not be appreciated by all, as many people generally consider looking at large paintings hanging well-lighted on walls easier and perhaps visually also more gratifying than peering at small books in tiny print, lying in cabinets. Yet this two-room show is essential to a well-grounded understanding of the overarching theme of the exhibition and as such demonstrates not only how thoroughly the curators have constructed the exhibition as a whole, but also how well they understand the topics they’re dealing with. Paper sources – on display are books, woodcut-prints, drawings, pamphlets, etc. – have always been one of the main channels by which any fascination for the esoteric generally or the occult specifically was sparked, sustained and transmitted to others and to other generations. The selection of shown sources is very relevant, ranging from Marsilio Ficino’s neo-Platonic works and Heinrich Khunrath’s Emerald Table to Emanuel Swedenborg’s many writings and the pamphlets of Joséphin Péladan. Such primary esoteric material is combined with many examples of literary and graphical sources (drawings, etches, woodblock-prints) that illustrate well to which considerable extent literature and the graphical arts appropriated esoteric thought, motifs and iconography. Examples displayed range from Dante’s Comedy to the poems of Charles Baudelaire and the stories of Arthur Conan Doyle, but include also etches of Albrecht Dürer and Hans Baldung Grien. By showing sources such as these, this small exposition offers an important two-fold insight: That occultism was not something to suddenly appear on the European stage, but rather a development that was a long time in the making, going back to Renaissance esotericism; and furthermore that literature and the arts have been engaging in esotericism since that time – in other words, that a relationship between the visual and literary arts and esotericism was already in existence by the time of Romanticism. Obviously by the nineteenth century and certainly in the twentieth the visual arts were taking their interest in esotericisms of their time, occultism and spiritism, to a whole new level, which is the central premise of this show, explored and visualised in the main exposition, entitled L’Europe des esprits, arts et littérature.

Europe of the spirits is aimed towards showing how the visual and also the literary arts were informed and inspired by and appropriated occultism. The tone is immediately set by a selection of dark drawings by Francisco de Goya. The first part is entitled Romanticism and the occult, but primarily develops the Romantic taste for the dark, wild, chaotic, haunting, gothic and otherwise rather heterodox side of things, which obviously also included occultism.

Francisco Goya, The Conjuration (The Witches), 1797-1798, oil on canvas, 43 x 30 cm, Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid. (Photo: Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid)

Thus the point is made that many Romantic artists gravitated rather naturally, more or less, towards occultism. Symbolism, the focus of the second part, is the period when certain modern artists really started to create occult art, that is, when they started to move beyond the mere use of established occult themes or tropes and towards developing a new and occultly informed iconography. Additionally to just reading or hearing about occultism, artists now became more or less personally involved in occult and/or spiritist milieus. In other words, occultism in the arts changed from being primarily a repository of information in which to find exciting or mysterious motives and tropes to something more of a worldview or lifestyle. This development reached its peak with the avant-gardes, the third part of the show.

Abstractions and other expressions of the avant-garde explores how modern artists continued on the path Symbolism had set out on, but moved beyond established forms and iconography to new forms and styles even. Obviously attention is paid to the connection between Early Abstract art and occultism and spiritism, particularly the impetus that the latter movements proved to be in certain artists’ move from figuration to abstraction. These artists, of which Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and Hilma af Klint are the most famous examples, and their art have already been the central focus of The Spiritual in Art. In 1986 the connection between spirituality – or rather esotericism – and abstract art was still very new and exciting and the show came hard on the heels of the seminal and influential study of Kandinsky by Sixten Ringbom.[4] A decade later the Schirn Kunsthalle focussed on the same period and group of artists with Okkultismus und Avantgarde: von Munch bis Mondrian 1900-1915,[5] while the same group moreover made its appearance in Traces du Sacré as well as now in L’Europe des esprits. The relationship between occultism and Early Abstract art is quite well established by now, and perhaps becoming rather stale. Yet it must be said that the curators of L’Europe des esprits have tried to find a new angle to this topic by including less known artists such as Maria Ender, Mikhaïl Matiouchine and Auguste Herbin alongside the more usual suspects Kandinsky and af Klint. In similar vein another usual suspect is on display, the book Thought-Formsby Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater and its colourful illustrations of thought-forms, but combined with something less frequently seen and just as relevant: colour-full conference designs by Rudolf Steiner explaining metamorphosis, thought-processes and the cabalistic Séphirot. Also the early avant-gardes are not limited to the abstract ones. By also including avant-garde artists who continued to work more or less figuratively, such as Tyko Sallinen, Alberto Martini or Paul Klee, the show does point out that others also engaged in occultism just as the abstract artists did.

Paul Klee, Demonic Young Lady, 1937, crayon and distemper on paper on carton, 45,6 x 30,9 cm, Bern, Zentrum Paul Klee. (Photo: D. R.)

The last part, Surrealist Constellations is a bit weaker than the earlier three, not so much in the art exhibited as in the direction indicated by that title. The curators do not quite make it clear how and why modern art’s obsession with occultism ends with Surrealism (or even if it did so). Nevertheless they have opted for an interesting array of artworks, including a separate room with spirit art and art brut. These forms of art, classified as ‘mediumistic art’ by Breton in the early 1920s, were much admired by the surrealists and played an important role in the surrealist exploration of automatic states and techniques. The rebranding of spirit art as ‘automatic art’ in Surrealism, for instance, showcases how for the surrealists the occult and the spiritual had become fully secularized. Unfortunately there are no hints as to how the fascination of the occult developed after 1950, something which Traces du Sacré did pay considerable attention to. One assumes that the chronological construct Romanticism + Modernism underlies the time-frame 1750-1950, and that the curators did not want to burn their fingers on postmodernism. That is a good choice as the show is imposing enough as it is and because the bonds between Romanticism and the avant-garde are apparent and make for a coherent whole. Perhaps next time, however, the Museum will provide visitors with a small pointer on what happened with occultism and art afterwards—because the fascination of the one by the other was far from over (and still is not today).

The majority of exhibited materials are paintings, with graphical works coming in second place. The literary angle takes the form of books shown here and there, for example by William Blake, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Edouard Schuré. It is not really developed in the main show, which, as it is developed in the side show detailing the paper trail, is not problematic. Amongst the paintings and drawings one will find a sculpture occasionally or perhaps a temple-model, but not much else. The prevalence of painting parallels the collection of the MAMCS itself, but also the current state of scholarship on occultism and the modern arts, in which painting has already received a significant amount of attention while sculpture or architecture lag behind, not to mention the performance arts such as theatre, dance and even music and cinema. It is not that such art disicplines are totally absent from the exhibition; the curators do point out the connections between the different disciplines of the arts, for instance with dance as developed by Loïe Fuller, Isidora Duncan and Rudolf Laban, and Rudolf Steiner. Photographs document these trailblazers and their dances. It is just that these arts all play second fiddle to painting, something they are frequently forced to do as painting is still considered the most eminent art form today. One can only hope that future exhibitions on such a grand scale will be devoted to the relationship between occultism and the performance and musical arts. Even more, one should hope for shows that focus on how occultism was in fact fascinated by the arts – because obviously admiration, inspiration, influence and appropriation went both ways. The products and objects of occultism, spiritism or esotericism generally usually only make their appearance in museums to illustrate developments in the ‘real’, that is canonised art movements, such as Symbolism and the avant-garde; this is also the case in L’Europe des esprits.

Yet in general the curators are to be commended for taking such a step forward, as they have certainly done with this show. This was achieved by taking a number of small steps, which all together make this exhibition stand out as a well-researched, comprehensive and valuable approach to the topic. For instance, the fact that masking terms such as ‘the spiritual’ are dispensed with is important. Spiritism and occultism are taken seriously as cultural forces in themselves, which had much more to offer than a mysterious iconography or some lurid ideas. The show’s emphasis upon the paper trail, embedding as it does occultism and spiritism in the larger overarching discourse of esotericism, testifies to the fact that all three of these movements – esotericism, occultism and spiritism – have now been upgraded to proper historical developments. Secondly, the curators show sensitivity to the differences between flirting with the gothic or heterodox, appropriating occult iconography and creating new occult art, providing room for a proper evaluation of the dynamic between a particular artist and their art, and occultism.

A third step taken is the choice to focus on Europe. Although the show also includes Scandinavian, Baltic and Eastern-European artists, obviously French and German art still form the heart of the displayed works (as they did in the other mentioned exhibitions). Nevertheless the aim to emphasize that modern art’s ‘fascination by the occult’, as they call it, was a pan-European thing, is commendable. Similarly to be praised is the effort to show that said fascination was furthermore shared across styles, schools, mediums and disciplines.

A fifth important step that has been taken is to highlight the presence and role of science in the contemporary discourses of the arts and occultism and spiritism. This forms the theme of the other small side show, entitled When science took the spirit’s measure. This two-room exposition emphasises that a fascination with the occult was not something beholden to the literary and visual arts alone, but rather a culture-wide phenomenon, with a particular strong presence in the sciences. Many scientists and intellectuals engaged in research of the phenomena of spiritism, also known as psychical research. Unfortunately the small exposition does not quite rise above the level of a collection of curiosa. A number of very interesting devices and machines are displayed, for instance from the Science Museum of Strasbourg University, but the exposition fails to fully explain what they were supposed to measure, what they actually did measure, how they were employed within the séances and how mediums and other spiritists reacted to such machinery. Moreover, while we are informed that modern artists were aware of psychical research, it does not quite become clear how, why and also when that occurred – only in the early twentieth century, as seems to be suggested, or also before that? And what did it result in? Admittedly these issues are clarified more or less in the catalogue, yet for those just browsing through the show it will remain somewhat of a mystery how psychical research was conducted and what it provided to science, occultism, spiritism and the arts.

Yet this concerns a side-show. All in all L’Europe des esprits is a well-constructed exhibition, comprehensive, tracing a broad path while pointing out many particularities and sketching relevant developments succinctly and clearly. I am sure that it will set the standard for a long time to come.

L’Europe des esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte, 1750-1950

Musée d’Art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg, France: 8 October 2011 – 12 February 2012

Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland: 31 March – 15 July 2012[1] Centre Pompidou, Jean de Loisy, & Angela Lampe (eds.), Traces du Sacré (Cat.), Paris 2008.

[2] LACMA & Haags Gemeentemuseum, Maurice Tuchman (ed.), The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (Cat.), Los Angeles & The Hague 1986.

[3] MAMCS, Joëlle Pijaudier-Cabot & Serge Faucherau (eds.), L’Europe des esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte, 1750-1950 (Cat.), Strasbourg 2011.

[4] Sixten Ringbom, The Sounding Cosmos: A Study in the Spiritualism of Kandinsky and the Genesis of Abstract Painting, Abo 1970.

[5] Schirn Kunsthalle, Veit Loers (ed.), Okkultismus und Avantgarde: von Munch bis Mondrian 1900-1915, Frankfurt 1995.

Quellennachweis: Tessel M. Bauduin, Modern Art Revisited: A Fascination for the Occult. Review of the exhibition L’Europe des esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte, 1750-1950, in: ALL-OVER, Nr. 2, März 2012. URL: http://allover-magazin.com/?p=810.