Mute existence, uncommunicable and exempt from any possibility of equality or commensurability (lacking any considerable middle ground with the social body) – an impossible proposition to uphold. It is an existence embedded only with a private sense, a sort of sensus privatus that even for Kant results only in madness. And what is madness, for instance in the context of the psychoanalytic situation, if not putting into speech the unspeakable, the transition of an a-communicable neurotic into the communicability of analysis? The reading, the mapping, and the speaking. The path from sensus privatus to sensus communis. Even as Kant’s certainty of common sense (the cognitive base of communality and sociality and the implicit presupposition of a naturally present and correct thought that finds its critique not only in Nietzsche but following his lead also in Deleuze) gives way to a sort of common non-sense the assertion of communality seems to persist.

The assertion of which could also serve as a cynical ‘good riddance’ to the exhibition Next of skin that finds itself even more communicable in its attempt of a-communicability. The neatly coded context of an exhibition space, an exhibiting event where the artworks form snares and obstacles for the viewer’s comprehension, fuel only the most frivolous conversational giggling from the young cultural intellectuals in attendance.

The exhibition presents four Slovene artists: Andrej Škufca, Živa Božičnik Rebec, and the duo Kladnik&Neon. It is curated by Tjaša Pogačar in collaboration with Marko Bauer, and consists of five artworks.

Cynical formulas scratch the surface that their artworks dexterously avoid. Not with profound depth or an elusive essence that art has woven through the many decades into its blanket of mystique, but with a surface that constitutes a completely different field than that of art.

There is no more beauty behind the unrepeatability of everyday banality, no more profundity in the surface of contingency, no more sense-less romanticism of Bas Jan Ader or the cynical ‘a-cynicism’ of NSK. There is even no more blatant transparency of critique. Instead, the works exhibit the banal banality. A vast surface or, rather, a stain-resistant plastic dish purchased on one of those infomercial-filled late nights of the past, where the stain is the beaten spirit behind the mysteries of life.

The surface does not emanate a communicable a-communicability. No sublime nor sublimation. It is cleansed of its authentic core, although cleanliness may not be the most suitable reference. It lies a-communicable through and through, a semblance of sense or meaning that is not decipherable by the spectator, nor able to be psychoanalytically analyzed. It is political, but only as long as it severs the Aristotelian tie between speaking and political being.

So what is exhibited? The exhibition layout in its clean and minimalistic design has a rather stacked effect: the artworks in a narrow exhibition space all face the entrance, making the usual walk around the exhibition space almost, if not completely, redundant. ‘Move along… nothing to see here folks’ could as well be the curatorial voice that my imagination (references to Kant’s economy of senses seem persistently to stalk me) insists on pinning to the curator.

The artwork in the foreground, the smallest, the starting point, is an object by Andrej Škufca, entitled sk234 (Fig. 1). The object evades recognition and identification as it consists of almost nothing else but recognizable elements of design. The object is therefore without an apparent or intended function, as much as without any particular art related a-functionality or disinterestedness so prominent in the classic lingo of aesthetics. It is neither an everyday object nor art, nor a provocation of anything but taste in general. It is simply lame; no extensive interpretation needed. It resists anthropomorphization to the extent that it would be inappropriate to say it does not intend to be anything more than it is since saying that would already ascribe it agency. sk234 is not indifferent, nor does it induce indifference in the spectator, but it is itself indifference that could point toward the implicit banality of consumer logic behind design, if that would not already imply a certain interest and purpose on its behalf.

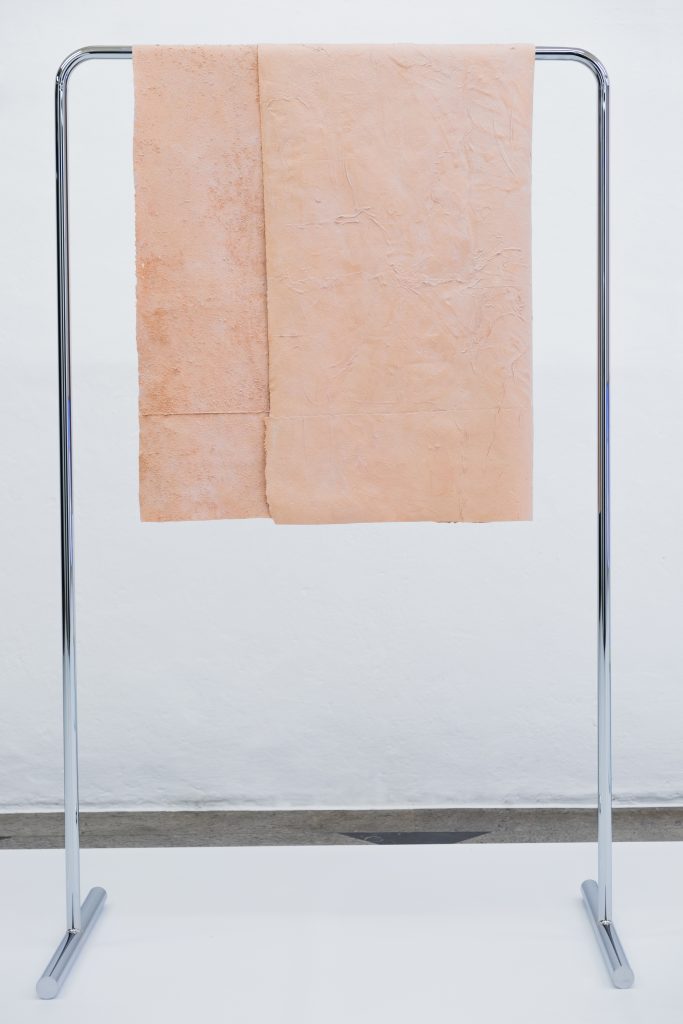

Fig. 2: Živa Božičnik Rebec, TOWEL 1, 2017, latex towel collection, cromed steal, latex, 160 x 100 cm. Photo: Lara Žitko.

Close to sk234 is TOWEL 1 (Fig. 2) by Živa Božičnik Rebec, a ‘latex towel collection’. It consists of a chrome-like stand and a hanging fold of latex that, according to the title, may resemble a towel with its hygienic intimacy of caressing one’s skin. The latex inscribes an association of caressed skin onto the towel itself through its pink/coral tone and wrinkly structure (inscribing the relation of caress-ness into the object’s own becoming). As the pattern of the latex differs on each side, and as these organic structures are disturbed by an inorganic straight line that resembles a manufacturing seam, the associated intimacy and its organicity fall apart in an indecipherable drama of inorganic surface structures.

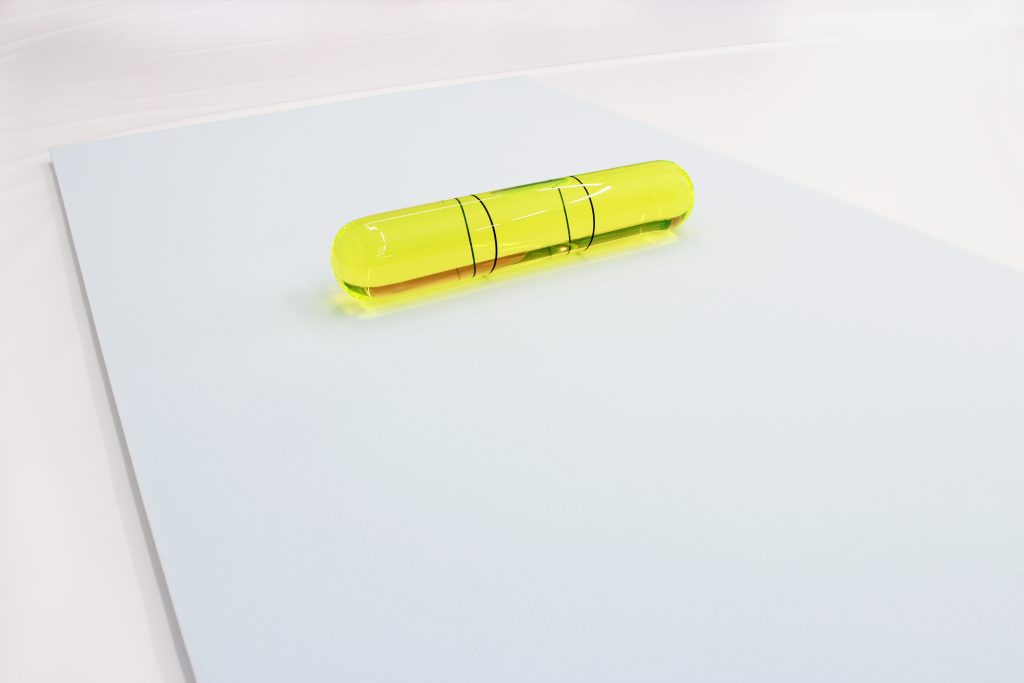

Spirit Level (Fig. 3), a piece by the same artist, consists of a hefty florescent object lying on a soft blue foam surface, resembling a yoga-mat. A similar referential dynamic as in TOWEL 1 takes place here. This presentation differs from the work’s previous presentation at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, where the object was placed on an upward-elevating foam with greenish surface structures looking like fungi-scales and accompanied by a photograph of a man with long ruffled hair, dressed in white, presenting the object on his palms with a meditative gaze. The reference to ‘spirit’ was a bit clearer and direct in this past presentation, whereas now it verges on disappearing as the ground placement, lacking the previously present topology of ascent, refers only vaguely to yoga. However, the structure of the work remains similar. The classic ascent to a desired spirit level (leaving the banal and pain-ridden earthly sphere behind) gives way to an expansion of a flattened or leveled sphere where the earthly and ideal collide and merge. It replaces the value of height with the level of balance where a completely technical approach is taken (thus the water-ruler). Spirituality here is an immanent and highly technical endeavor: in the flattened world truth, god and the afterlife become things of measure and proportion. It coincides with the expansion of the egocentric subject through its attempt to better him/herself by constantly tweaking his or her everyday routines (be it dietary, fitness, etc.). A balancing act of tweaks and tricks that brings the spiritual down to the level of personal wellness.

Fig. 3: Živa Božičnik Rebec, Spirit Level, 2017, glass, colouring, water, foam, 130 x 80 cm. Photo: Lara Žitko.

This leads us to the last two works by Kladnik&Neon, where the previously mentioned tweak in the presentation (the reduction to a yoga mat) gets its glorified exposition. Safe space, a CGI animation, and Quia ego sum tanti (‘Because I’m worth it’), a print on tarp (Fig. 4), both address fitness as a process of degradation of the Latin saying ‘mens sana in corpore sano’ (‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’). Here, mind and health get lost in the inflation of the body: its endless growth of muscle that moves toward a point where expansion surpasses the question of taste and human form. Something that is also reflected in the re-envisioned classicism of the artists’ design that is polished to the point of surpassing any notions of kitsch, while still remaining firmly rooted in the this-worldliness of its own neoliberal logic.

Fig. 4: Kladnik&Neon, Quia ego sum tanti, 2016, print on tarp, 150 x 250 cm; Kladnik&Neon, Safe space, 2016, 3D motion graphics, 6’8”, loop. Photo: Lara Žitko.

What binds the totality of the exhibition together is a tendency to reach, if not actually realize, a surface where there is no depth of essence nor height of truth. No dark mysteries of art nor gleaming light of science. A surface that radically avoids meaning although it constantly creates a semblance of it. It speaks, but only as long as we are the ones putting speech onto it. By itself it is a-communicable. Nothing worthy to discuss (with or about).

In this, the works defect from the already proliferated use of Jacques Rancière’s conception of the politics of aesthetics in local and international art production. If there is anything political in this exhibition, it definitely does not concern the emancipation of a spectator. Instead it addresses that which Rancière’s conception of politics is lacking.1

The artworks namely address the strange ambivalence surrounding one of Rancière’s main presuppositions for his endeavor: radical equality. The latter seems to replace the idea of consensual workings of a body politic with one of discord, thus challenging the anthropologic foundation of politics (referring back to Aristoteles’ idea of a bios politicos on which politics is founded). Yet it also paradoxically reinstates a similar foundation as that of Aristotle as it entails a sort of primary understanding that disregards the exclusions made by the logos:

“There is order in society because some people command and others obey, but in order to obey an order at least two things are required: you must understand the order and you must understand that you must obey it. And to do that, you must already be the equal of the person who is ordering you. It is this equality that gnaws away at any natural order”2.

Rancière’s conception is limited to a subject with ‘an intention to communicate’3, to ‘a speaking being’4. Here, communicability re-enters the scene and simultaneously pushes all the domestic pets and other liminal beings of understanding out of the political situation that Rancière envisions as a solution to the excluding logos.

The a-communicable is, yet again, not a possibility for political consideration. And if there is any political potential in it, the path through the banal banality, that which this exhibition attempts to traverse, poses a way to explore it. It tests the limits of both interestedness and disinterestedness, aiming at those rare moments in contemporary art when its elusive character provokes one to ‘kick it’ senseless – as little sk234 unintentionally was at the exhibition opening.

To conclude, there is not much to see, and what there is, does not require a lot of strain. Perhaps the spectator of the 20th century will not be abolished by way of engagement or action, but of atrophy.

Domen Ograjenšek is a Slovene freelance writer and curator, currently based in Vienna, where he continues his studies as a doctoral candidate at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, researching the political impossibilities of contemporary exhibiting tactics. He has worked as an editor of Šum – Journal for Contemporary Art Criticism and Theory, and Art-area (a bi-monthly radio show dedicated to contemporary art on Radio Študent), and has been part of exhibition projects.

Next of Skin, 10.–23.4. 2017, Glass atrium of Ljubljana Town Hall

1 “The images of art […] help sketch new configurations of what can be seen, what can be said and what can be thought and, consequently, a new landscape of the possible.”, Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, London and New York 2009, p. 103.

2 Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, Minneapolis and London 1998, p. 16.

3 Jean-Philippe Deranty and Alison Ross, The Evidence of Equality and the Practice of Writing, in: Jean-Philippe Deranty/Alison Ross (eds.), Jacques Rancière and the Contemporary Scene, London and New York 2012, pp. 1–14.

4 Todd May, Rancière and Anarchism, in: Deranty/Ross 2012, pp. 117–128.