Benjamin Patterson, who saw over fifty years of experimental art production as a Fluxus co-founder and artist, passed away this summer. Born in Pittsburgh May 29, 1934, Patterson was an African-American bassist with limited professional opportunities in segregation-era United States. Instead, Patterson circumvented existing racial barriers by relocating to Canada and performing with symphony orchestras, at which point he took closer interest in electronic music.[1] A trip to Germany redirected the course of his career to experimental art production after a negative encounter with acclaimed Karlheinz Stockhausen. The fallout was brief. Shortly thereafter, he attended and even performed in Cologne alongside major persons such as American experimental musician John Cage. Patterson later held a central role to the formation and continuation of Fluxus, a group associated with anti-art, neo-dada and proto-conceptualist ideas in performance.[2]

A principal Fluxus artist, Patterson supplied details about the group’s history and choices of media in numerous interviews over the years. For example, his conversation in the US Army magazine Stars and Stripes introduced Fluxus to general audiences in Wiesbaden. Emmett Williams, a fellow Fluxus artist and the magazine’s editor, also partook in the “tongue-in-cheek” conversation on their antics.[3] More recently, Patterson contributed significantly as the creative director of Fluxus’ fiftieth celebration in Wiesbaden, its adoptive birthplace.[4] Obituaries following Patterson’s passing remark upon his prominent role, his many firsts, and also poetically treat his overlooked contributions to histories of experimental art.[5] In this article, I contribute to reflections on Patterson’s significance by concentrating on one of many interviews from his lifetime.

Indeed, I argue that his self-authored interview “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” from 1991 became a linchpin from which Patterson developed a public platform and tangible presence within Fluxus history.[6] I focus on the life of the essay and connect it to Patterson’s engagement with writing as central to his art practice. Exploring moments behind this publication provides an alternative way to respond to discussions related to Benjamin Patterson’s art career — particularly, his absence within Fluxus narratives.

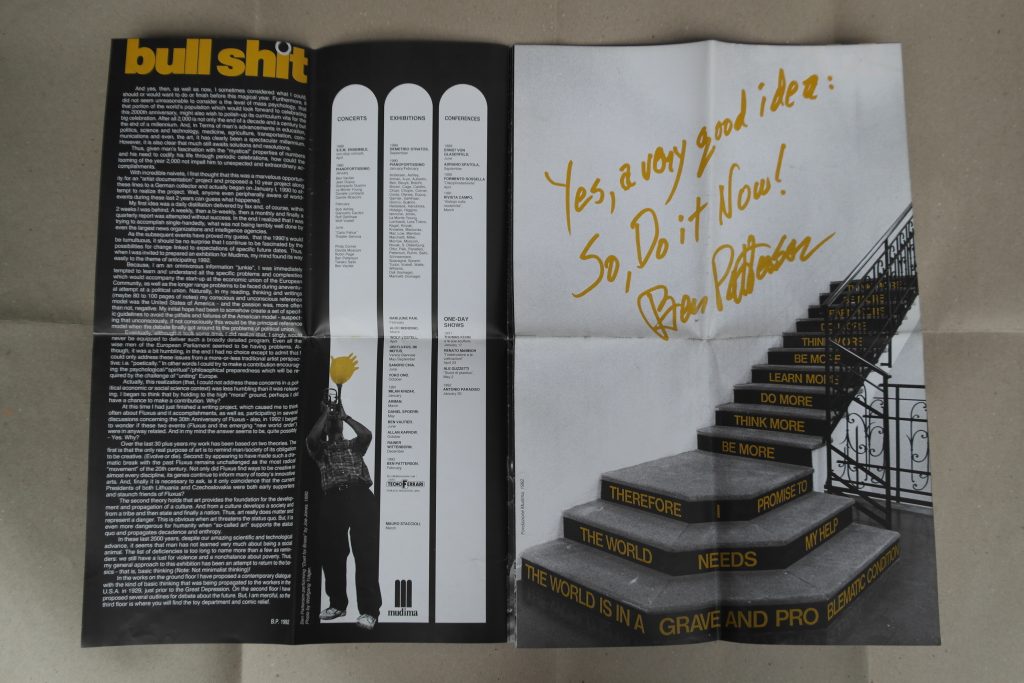

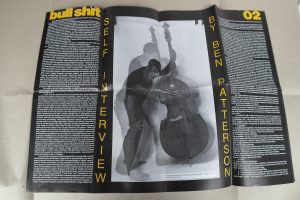

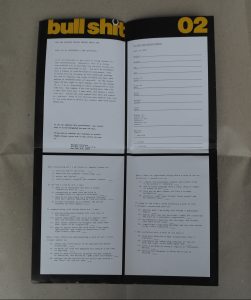

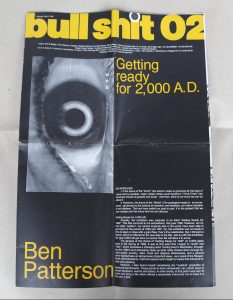

I begin with the second appearance of “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” as “Self Interview.” This text reappeared for Patterson’s first solo show in 1992 at Fondazione Mudima in Milan, which published the exhibition-specific periodical Bull Shit. Patterson’s special issue of Bull Shit, titled Bull Shit No. 2, featured two texts by him, several images, and artwork as supplemental material for his show Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. This issue is the only time that any of Patterson’s other writing accompanied the interview, meaning that he was the sole author of the issue. The multiple appearances of this interview extended its life, accessibility, and thus contexts behind Patterson’s relationship to art making. In this essay, I link all five lives of his interview to consider writing as central within his art practice.

Of note, “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” first debuted as a standalone article in Kunstforum International in 1991, propelling his profile to a German-speaking public. Patterson republished it in English and under the heading “Self Interview” (1992) in Bull Shit. Its third and fourth appearances in 2011 and 2012, in From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany and Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us respectively, existed alongside a wave of scholarly interest in highlighting his role as a leading Black experimental artist. Its fifth, and now final, form appeared in 2013 as “Fortsetzung,” in which Patterson updated audiences about his rise in popularity, a rise leading him to assert he, “no longer enjoy[ed] anonymity.”[7]

Fig. 1: Benjamin Patterson, Bull Shit No. 2, cover page, featuring “Background” by Benjamin Patterson, February/March, 1992.

In 1992, Patterson reused the entire unaltered text from his 1991 self-authored interview. It functioned as the main essay for his issue of Bull Shit, and for his multileveled solo exhibition at Fondazione Mudima. The interview progressed through a series of planted questions, detailing Patterson’s career overview as well as positing judgments about Fluxus as a collective. His choice to republish the interview indicates a desire to familiarize different audiences with his knowledge of Fluxus history. It similarly provides an additional layer for approaching how Patterson conceptualizes ideas. His special issue Bull Shit. No 2 includes a separate text titled “Background,” which precedes “Self Interview” and articulates themes integral to his exhibition Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. In an attempt to lay bare his exhibition framework, Patterson’s texts performed like scaffolding, providing entryways for audiences to understand practices and theories for an exhibition prompted by the end of a decade and a century.

The circumstances behind the interview’s second life, however, in Bull Shit remained unannounced in the issue. Neither Gino di Maggio, an enthusiastic Fluxus collector and founder of Fondazione Mudima, nor Patterson, elaborated explicitly on such intricate points as editors. They listed it simply as “Self Interview,” and the eponymous in-line reference weakly clues new audiences to its original title. The text’s introduction also offers little support for a deeper understanding of its preexistence. I am choosing to magnify its presence, reading it visually and textually as part of Patterson’s practice in writing and viewer engagement. Writing and imaging were critical modes of communication that undergirded much of his early works on paper, his puzzle poems and his operas. It is therefore productive to treat this interview as a comparable moment within his creative process.

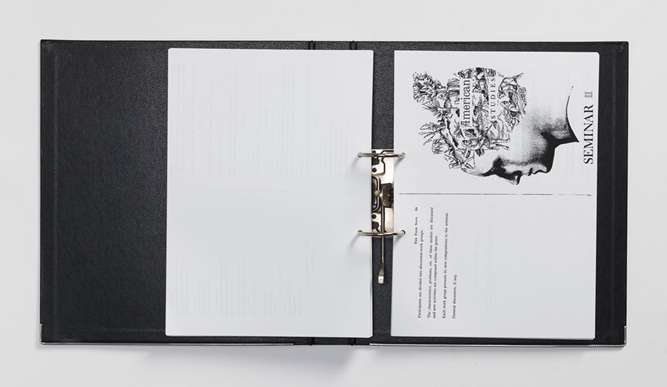

Fig. 2: Benjamin Patterson, “Seminar II”, Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performance and Other Projects 1958-1998. Black binder, white facsimiles. 32 x 29 x 5 cm.

Two quintessential examples from his oeuvre are the anthology Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performances and Other Projects 1958-1998 (1999) and Methods and Processes (1962). Prose is a distinctive characteristic in his Black and White File. Readers encounter heavy amounts of text as guidelines to performances or as texts for events. Comparatively, his first artist book Methods and Processes marked a “sort of the return to visual work, as it were,” evident from his pairing of texts and images for interpretative exercises.[8] Patterson’s comprehensive assembly of materials reveals that he approached publishing as a way to ensure accessibility.[9]

Whereas Patterson did foreground some explanatory details at the introduction of “Ich bin froh” (and its subsequent titles), I am particularly interested in what he visualized or obscured. Accessibility may offer resources from which to build upon, but it cannot always clarify context. At the outset, Patterson wrote “Dieter Daniels suggested that he would like to do a piece on Benjamin Patterson in a special Fluxus issue of Kunst Forum,”[10] Patterson’s dislike for interviews led to Daniels suggesting that he “do the whole interview of myself by myself.”[11] Outlined in this playful, albeit serious, first and third-person work, are ideas and accounts; left unstated are the editorial and visual decisions impacting the issue.

Patterson communicated working theories about his practice in his special issue of Bull Shit, and established the tenor of the exhibition through visual forms. His “Background” text, a separate and preceding text as I mentioned above, supports my first point. In gray, he wrote: “Actually, this exhibition was originally to be titled ‘Getting Ready for 1992.’ This title occurred to me somewhere, mid-year 1990. However, as it is now clear, neither I, nor almost anybody else in the world, have been able to get ready for the events of 1990 and 1991.”[12] “Background” laid a foundation for a show framed by the ensuing years, beginning with the 1990s and concluding at the millennial turn. If the single, disembodied eye on the issue’s cover was not distressing enough, Patterson’s words suggested the need to brace oneself.

Rather than frighten readers, Patterson sternly suggested that the present and future moments were ripe for productive conversation about social conditions. Shifting back further than 1992, he cited 1989 as the real point of departure for Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. at Fondazione Mudima. “It was at that point that I began to ’smell’ that ’odor’, [sic] which precedes a changing wind,” he noted about living in New York City at a time of escalating social problems.[13] Patterson found himself surrounded by class and racial divides that worsened under President Ronald Reagan’s “Reaganomics.” Reagan’s neoliberal economic policies of lower taxation and de-regulation were critiqued widely as placing business before people. Just as well, 1989 signified more than US trends. It evoked a sense of relief and hope attached to the demolition of the Berlin Wall, which stood as a remnant of divisiveness from World War II. Its “fall” subsequently foreshadowed Germany’s reunification, which crystallized a sense of progressive change in the western global imaginary.

The impression of progress ran parallel in Patterson’s special issue as readers advanced the folios. The spread contained forms with literal, and in my opinion, metaphoric meaning. Once individuals turned from the cover page to the next, they encountered a photo of Patterson trumpeting to an undetectable horizon. As he plays a trumpet covered by a plastic glove, he stands beneath three sections of forthcoming events at Fondazione Mudima that resemble white columns: “Concerts,” “Exhibitions,” and “Conferences/One Day Shows.” Each column forms a white silhouette of a classical arch, repeating Mudima’s iconic black logo at the bottom, which also situates Patterson’s clipped image within a symbolic context of tradition, invention, and grandeur.

To the right-hand side, an installation photo of a staircase with vinyl letters covers the entire page. The image indicates that visitors would travel up a staircase of declarations to view other exhibition works. This one in particular had a bulky bullnose that narrowed after three steps. The ordinary movement up a staircase becomes an ascendance across elongated assertions and declarative vinyl on every riser. It recalls text from “Background,” such as Patterson’s comment that beginning of new years leads to a type of introversion for “considering the ‘mystical’ properties of temporal benchmarks.”[14] Like New Year’s resolutions, one moves from premise to affirmation.

The first step states, “THE WORLD IS IN A GRAVE AND PRO-BLEMATIC CONDITION.” The next step, “THE WORLD NEEDS MY HELP,” signals a move towards solutions. Patterson wrote out in vinyl for each subsequent step: “THEREFORE I PROMISE TO/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE/ DO MORE/ LEARN MORE/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE/ DO MORE/ LEARN MORE/ BE MORE/ THINK MORE.”[15]

Viewed together, the verso and recto pages imply upward movement and resonate with Patterson’s conclusion at the end of “Background.” Among other topics in the text, readers would also learn that Patterson had initiated a ten-year artist documentation project to capture the onslaught of worldwide events. The initiation of the Gulf War by the US (1990); German Reunification (1990); and the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in apartheid South Africa (1990) were historical shifts that took Patterson’s attention. Related to the development of the European Union, his featured works in the show were contributions for “encouraging the psychological/‘spiritual’/philosophical preparedness which will be required by the challenge of ‘uniting’ Europe.”[16]

A supplement to the exhibition, his special issue “Bull Shit No. 2” similarly performed ideas of preparedness and reflection. Each text within, “Background” and “Self Interview,” elaborates on Patterson’s theories of art and Fluxus history. He flatly laid out parameters of both, sharing that he completed a “writing project” prompted by Fluxus’ upcoming thirtieth anniversary in 1992.[17]His first theory was that art existed out of the humanity’s need to be creative, or as he stated “evolve or die.”[18] Second, art created a basis from which culture extended by “development and propagation.” Taking the position that positive social change moved slower than societal development, Patterson envisioned this exhibition as his “return to the basics,” or using art for necessary progress.[19] This “return,” I believe, also references actual changes in his own life.

Getting Ready for 2000 A.D. occurred two years of sustained momentum with his career. After relocating to Germany, Patterson already had two recent solo shows, completely severing his so-called “retirement from the unstable life of an experimental artist in New York” since the mid-1960s.[20] Patterson described the years between 1965 and 1988 as the period where he pursued a normal life, shorthand for parenthood and a regimented lifestyle. The life of a Fluxus artist offered little financial ability, and so he took up library, director and freelance positions over the years.[21] All the while, he showcased or performed a range of works at varying institutions.[22] His solo show “Ordinary Life” (1988) at Emily Harvey Gallery signaled his “return” to working as an artist, jumpstarting a tremendously prolific period to come. As the gears turned, his interview created unobstructed space for Patterson to enunciate his experiences and articulate a history of Fluxus.

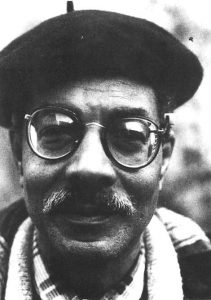

The interview became an opportunity to fashion a public identity and develop an archival footprint in public. For example, Kunstforum International’s “Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben” includes a stunning monochrome portrait taken by Wolfgang Träger, an acclaimed documentary photographer. Patterson smiles pleasantly at the camera while donning a wool beret, and a plaid shirt and sweater combo beneath a coat — sartorial cues of an urbane artist. After Träger’s close-up follows reproductions of Patterson’s artwork or material supporting exhibitions, from an exhibition card to performance documentation. The last images are of assemblages and installations, and the visibility of this material not only serves as evidence of works but also an unrestricted art practice.[23]

Patterson’s flexible approach to material and objects is noticeable in the interview’s format change in Bull Shit, and suggests he considered the context of its second republication. Not only did he extend its afterlife, but he also added another layer in presentation. With an entirely different set of images to accentuate his narrative, the interview appeared in English and served as connective tissue between himself and English-speaking audiences. Patterson’s customized issue “Bull Shit No. 2” doubly reflected the artist-led direction of the periodical Bull Shit at the foundation.[24]

Bull Shit positioned the voice of the artist front and center. In this way, it recalls western conceptualist strategies of curating during the late 1960s. Lucy Lippard’s and Seth Siegelaub’s portable catalogues, created from artist-submitted material, are just two major examples. Fluxus artist Dick Higgins’ Something Else Press was also integral to circulating artist writing and work. In the context of the move to reach audiences beyond the “white cube,” Patterson’s special issue was a setting to expand networks and information sharing.

Readers of any interview version would learn about Patterson’s origin story; a narrative beginning with his ambitious attempts to integrate US symphony orchestras, and his subsequent involvement as a Fluxus artist. Patterson’s planted questions were followed by descriptions of a lifetime of achievements that bordered on the epic and personal history, essentially creating a roadmap of his experiences. Detailed encounters manifest through memory, such as Patterson’s responses to living in New York or his subtle references to racial experiences that spur questions about Fluxus’ internal harmony: “to varying degrees they all became friends of a sort. But now I recognize that we simply did not share the deep-rooted (albeit hidden) alienation that I lived with as the only black in this crowd.”[25]

His use of the term “hidden” implies a scarcity of moments in which he comfortably spoke with his peers about race. Race was one of many constructed categories informing Patterson’s positionality. He was Black, middle class, college-educated, travelled and so forth. Personally, Patterson acknowledged race as relevant, which he also linked to his use of humor.[26] The slippery balance between indirect referencing and verbalization, revealing and concealing, presence and absence, also plays out in the rest of “Bull Shit No. 2.”

Unlike the clear portrait by Träger in Kunstforum International, Italian photographer Fabrizio Garghetti’s photograph of Patterson in Bull Shit seems hollow and illegible. In this moment, Patterson re-performed Variations for Double Bass during 1990 in Verona. The photograph echoes Patterson’s active presence in art-making by shifting the focus away from his artistic identity to his bodily movement. Printed evenly between each page, the image also inflects the context of the surrounding text. The three semi-transparent Pattersons, standing, playing and reaching out, link with his listing of artistic influences in the interview. The placement of such an image supplies more contexts for it and its neighboring text.

Similar moments occur throughout the following pages, such as a photo of Patterson leading blindfolded audiences along the streets matching his critique that Fluxus artists never reached out to him about civil rights marches. If art is generative and serves the needs of social development, Patterson suggested that Fluxus failed in this regard. He stated, “All [Fluxus] really did with its reputation for radical aesthetics was to provide a safe refuge and masks for a bunch of well meaning artists.”[27] As a platform in which he could concretize his presence and voice in Fluxus to a wider public, “Self Interview” pre-emptively addressed the biographical and the personal.[28]

“Self Interview” is a negotiation of Patterson’s history within Fluxus’ history. It thereby familiarizes readers with a certain level of visibility prior to, and after 1988. Thus, photos of his re-performances, work and installations, could engender conceptual and practical questions. Who did Patterson envision as his audience? Who was his public?[29] What was the reception of his work in the past, at that moment, and today? To whom was he visible or invisible and how does that affect contemporary engagement with his work? How fully does the historical record account for his international art practice? More scholars are considering similar sets of questions as Patterson’s profile rises.

Patterson’s interview reappeared nearly a decade later once intellectuals committed to emphasizing his artistic importance. Submitted by Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, the 2011 anthology From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany featured the interview with a preface to clarify her inspiration. To Oliver, Patterson was possibly “the ‘godfather of black performance traditions’.”[30] Oliver utilized the interview as a way to amplify Patterson’s voice, this time in book format and with two photos of his performances.[31]

“I’m Glad You Asked That Question” prepared new audiences for Oliver’s

exhibition, Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us, that opened November 6, 2010, at the CAMH. His first US retrospective, the exhibition and catalogue established a US scholarly context around his history as a Fluxus artist. Accompanying the interview were topical essays addressing aspects within his work – from lenses of conceptualist theory, music and chance, to Zen. The fourth iteration of Patterson’s interview became firmly grounded within a US art historical context.

His last version, however, diverges significantly in terms of subject and presentation. A follow-up to his 1991 interview, “Fortsetzung” is Patterson’s more recent reflection on his heightened profile. In 2013, “Fortsetzung” appeared in the Nassauischer Kunstverein’s exhibition catalogue Benjamin Patterson: Living Fluxus. Operating with a similar logic as the CAMH’s catalogue, readers encountered Patterson’s externalized thoughts. He asked himself, “Now you propose to continue with more questions and answers. Why?” His answer? “Because, again, in this 50thanniversary year of Fluxus there have been many, many interviews… and again, most often, asking more or less the same questions.”[32] Patterson implied a lack of new lines of inquiry on part of intellectual curiosity in the movement and himself. Much shorter than his first interview, “Fortsetzung” concludes by asserting that Fluxus’ challenges to the parameters of art have “kept Fluxus alive and continues to inspire younger generations.”[33]

His final conclusion seems abrupt, even abridged. Yet, in a practical way, Patterson’s appeal to Fluxus’s reception forestalls need to endlessly address basic questions. Just as Patterson concluded “Bull Shit No. 2” with his piece How the Average Person Thinks About Art (1983) – using art as a central form of engaging with history – Patterson’s written conclusion of “Fortsetzung” gestures for the need to move past biography to his work.

[1] Patterson was principal bassist with the Halifax Symphony Orchestra and Ottawa Philharmonic Orchestra. He also worked as a conductor for the Philharmonic Orchestra.

[2] Benjamin Patterson, I’m Glad You Asked Me That Question, in: Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.), Benjamin Patterson: Born in the State of FLUX/us, Houston (TX) 2012, p. 108–116.

[3] Emmett Williams, WAY,WAY, WAY OUT, in: The Stars and Stripes, August 30, 1962, p. 11. The interview was published prior to Fluxus’ festivals between September 1st to the 23rd.

[4] Histories of Fluxus accept 1962 as the year for the “official” birth of Fluxus, meaning that work and performances were then associated under the “Fluxus” term that George Maciunas first conceptualized as the title for a magazine in 1961, and then used publicly in writing June 1962 at the festival Aprés Cage: Kleinen Sommerfest Wuppertal.

[5] Andrew Russeth, Ben Patterson, Cornerstone of Fluxus and Experimental Art, Dies at 82, in: Art News, June 27, 2016, unpaginated; Hannah B. Higgins, On Not Forgetting Fluxus Artist Benjamin Patterson, in: Hyperallergic, July 6, 2016, unpaginated; Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Peeping in the Vacuum Left in that Space of ‘Darker than Blueness’ – On, Of, For, With Ben Patterson, in: Contemporary And, July 11, 2016, unpaginated.

[6] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Dieter Daniels (ed.), Kunstforum International, Fluxus: Ein Nachruf zu Lebzeiten, Nr. 115, September/Oktober 1991, p. 166–177; Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, in: Gino di Maggio and Benjamin Patterson (ed.), Bull Shit, No. 2., special issue, Milan February/March 1992, unpaginated; Benjamin Patterson, I’m Glad You Asked Me That Question, in: Maria I. Diedrich/Jürgen Heinrichs (ed.), From Black to Schwarz: Cultural Crossovers Between African America and Germany, East Lansing (Michigan) 2011, p. 335–349; Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.), 2012, p. 108–116; Benjamin Patterson, Fortsetzung: Ich bin froh, dass Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Elke Gruhn/Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden (ed.), Benjamin Patterson: Living Fluxus, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 32–35.

[7] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben: Fortsetzung*, Elke Gruhn/Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden (ed.) 2013, p. 32–33.

[8] Benjamin Patterson, in: Oral history interview with Benjamin Patterson, 2009 May 22, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[9] Patterson self-published Methods and Processes in 1962 while in Paris, and published Black and White File: A Primary Collection of Scores and Instructions for His Music, Events, Operas, Performances and Other Projects 1958-1998while in residence in Wiesbaden-Erbenheim with collector Michael Berger.

[10] Benjamin Patterson, Background, in: Gino di Maggio/Benjamin Patterson (ed.), Bull Shit No. 2, special issue, Bull Shit, Milan February/March 1992, folio 1.

[11] Ibid., folio 4.

[12] Ibid., folio 1.

[13] Ibid., folio 1.

[14] Ibid., Cover page.

[15] Ibid., folio 3.

[16] Ibid., folio 2.

[17] Ibid., folio 2.

[18] Ibid., folio 2.

[19] I am exploring his idea of radicalism and radical art in my dissertation, WHO TAUGHT YOU TO THINK (LIKE THAT): Benjamin Patterson’s Conceptual Aesthetic, University of Texas at Austin, in process.

[20] Benjamin Patterson, Ich bin froh, daß Sie mir diese Frage gestellt haben, in: Dieter Daniels (ed.), Kunstforum International, Nr. 115, September/October 1991, p. 166–177. Benjamin Patterson had two exhibitions at the Emily Harvey Gallery in New York, Ordinary Life (1988) and What Makes People Laugh? (1989). Patterson mentions his retirement within his interview.

[21] 1967 is the year in which Patterson received a Masters in Library Science from Columbia University.

[22] For a chronology, please see Meredith Goldsmith, Chronology, in: Valerie Cassel-Oliver/Contemporary Arts Museum (ed.) 2013, p. 240–253. Goldsmith’s chronology of Patterson is a solid primer into his professional career.

[23] This interview includes a photograph of Educating white Folk (1988), which exemplifies humor as an important strategy with its own set of politics. In fact, he stated in his interview that “I prefer to use humor as it often provides the path of least suspicion/resistance for the implanting of subversive ideas.”

[24] Notably, Allan Kaprow had a solo show titled “7 Environments” at Mudima. His special issue included self-authored writing. Artist Takako Saito, and even Ben Vautier’s tongue-in-cheek “issue 0,“ are examples.

[25] Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, unpaginated. “They” refers to La Monte Young, Jackson Mac Low, and pop or dance artists and so forth.

[26] In his interview, Patterson stated “Please know that we blacks used satirical humor as a form of protest.”

[27] Benjamin Patterson, Self Interview, unpaginated.

[28] Valerie Cassel Oliver, On Ben Patterson, 333.

[29] With regard to New York City, Patterson noted that audiences were comprised of about twenty frequenters of Fluxus activities.

[30] Valerie Cassel Oliver, On Ben Patterson, 333.

[31] The accompanying photos were Variations for Double Bass and “First Symphony Performance” accordingly.

[32] Fortsetzung, 32 (German) & 34 (English). The German version has a photo of Patterson giving a public interview in 2012. Italics are my own.

[33] Ibid., 33 (German) & 35 (English).